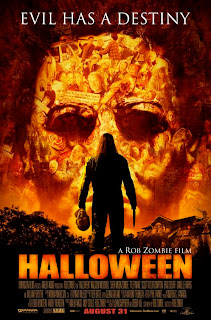

Dir. Rob Zombie

After massacring his family on Halloween, disturbed 10 year old Michael Myers is committed to a mental institution. 17 years later, he violently escapes and heads back home to Haddonfield to find his baby sister Laurie, brutally murdering anyone who crosses his path.

In November 2005, Halloween producer Moustapha Akkad and his daughter, Rima Akkad Monla, were killed at a wedding party when Al-Qaeda bombed the Grand Hyatt in Amman, Jordan. As the champion of the series since its inception, his tragic death was a blow for the future of the franchise. This, coupled with Dimension Film execs realising (maybe) the error of their ways with Halloween Resurrection, looked set to see the end of the Halloween films. However, following a trend of remaking old horror films from the Seventies and Eighties such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Black Christmas, Dawn of the Dead, The Hills Have Eyes, The Amityville Horror and When A Stranger Calls, producers recognised that Halloween was still a marketable name and decided to reboot/re-imagine/remake/reconceptualise John Carpenter’s landmark slasher.

As the director of the new version of Halloween, Rob Zombie attempts to explore and deconstruct the man behind the mask – relentless killer Michael Myers. By delving into Myers’ troubled childhood and his darkly dysfunctional family, Zombie attempts to address the issues that made Myers the merciless killing machine he grew up to be and show how someone could possibly commit such atrocious acts of devastating brutality. In his career as a filmmaker thus far, Zombie has always proved adept at presenting dark, twisted characters and offering glimpses into what makes them tick. He demonstrates a sort of understanding with those who exist outside of mainstream society, ostracised from normality and ensconced in freakishly carnivalesque lifestyles. Serial killers, outsiders and freaks are his schtick and often form the most interesting aspects of his work. Presenting the ruthless redneck killers featured in House of 1000 Corpses as the protagonists in its follow up, The Devil’s Rejects, was a daring move, and few directors could have pulled off such a feat.

It came as little surprise then when he announced his involvement with the remake of Halloween, and his intention to explore the childhood of its antagonist Michael Myers. Villains have always been the more fleshed out characters in Zombie’s films – he shows more of an interest in them than his ‘heroes.’ This aspect of probing Myers’ fractured mindset and background is the basis of the remake and perhaps it’s most original and compelling segment before it eventually descends into extreme violence and tensionless bloodletting.

A relentlessly grungy and grimy aesthetic depicting the Myers’ residence and lifestyle informs the film. Interiors are cluttered with all manner of bric-a-brac and later on when the film unspools as an extended chase scene, this clutter and structural disintegration works to create a sweaty claustrophobia, enhancing the stiflingly grim tone and driving home the sadistic violence. The film is constructed around a lengthy ‘prologue’ in which Myers’ childhood, the murder of his family and his subsequent incarceration and counselling with Dr Loomis is played out. When Michael escapes and Zombie returns the story to the familiarly cosy suburban landscape of Haddonfield and begins segueing Carpenter’s original story of a killer stalking teenagers into the mix, the second act feels very rushed. There is no build up to anything. This entire part of the film feels like a hyper-condensed version of Carpenter’s. The film’s strengths are actually when Zombie veers off from the familiar formula and does his own thing; puts his own stamp on the story. While it is interesting to see him recreate some of the iconic scenes from the original, it feels a little flat. Other scenes in this section of the film though, such as the murder of Laurie’s foster parents, are so intense, barbaric and effective because Zombie has the confidence to infuse his own vision into the story. Subtlety suffers though, and many of these scenes aren’t particularly suspenseful – but they do create a wallop of an impact. At times the camera seems to sense Myers’ rage and frenziedly shakes as it gazes at his shockingly realised bloodbath. The third act, while no less violent, is essentially a taut chase scene and Zombie aptly creates tension.

Myers is presented as a sensitive, shy child with worryingly violent tendencies (he kills small animals, usually a sign of psychopathic personality disorder). His mother works as an exotic dancer to support her family, his sister has no time for him, and his tyrannical step-father abuses the family, physically and emotionally. In his presentation of Myers’ dysfunctional family, Zombie seems to be saying that though many people have been dealt a shit deal in life – it is only a few whose inability to deal with it and see beyond it that become inherently corrupted. That’s not to say that Halloween is an insightful and nuanced deconstruction of human psychology. It isn’t – far from it in fact, as sometimes it feels one-dimensional, even caricaturist – but it’s all carried off with such besmirched aplomb, Zombie makes it work. It’s pop psychology by numbers, but in the context of a Rob Zombie film, it further showcases the director’s willingness to explore sleazy, disturbed characters and the sordid surroundings they exist in.

As the young Michael Myers, Daeg Faerch brings a quiet intensity to the fledgling killer. As his put-upon mother, Sherri Moon Zombie's sympathetic performance highlights Deborah Myers’ down-beaten resignation and begrudging acceptance of her life - she does what she can to hold everything together, but she's always up against it. Malcolm McDowell is an interesting Dr Loomis, though he isn’t given much to do except spout Donald Pleasence-isms about Myers’ inhumanity and devilish black eyes, and to say Tyler Mane’s adult incarnation of Myers is an imposing, formidable sight is an obvious understatement. Gone are Carpenter’s subtle placements of the killer at the edge of the screen, and in evidence are Zombie’s presentations of Myers as a barraging, relentlessly brutal bulldozer.

While Zombie’s Halloween has its flaws, it still manages to exemplify the directorial showmanship of Zombie and mark him as an interesting filmmaker with unique vision. His Halloween might not do as much justice to Carpenter’s original as many would have hoped, but as a Rob Zombie film, it follows on perfectly from the likes of The Devil’s Rejects, in the director’s ongoing obsession with submergence in the seedy underbelly of American society.

After massacring his family on Halloween, disturbed 10 year old Michael Myers is committed to a mental institution. 17 years later, he violently escapes and heads back home to Haddonfield to find his baby sister Laurie, brutally murdering anyone who crosses his path.

In November 2005, Halloween producer Moustapha Akkad and his daughter, Rima Akkad Monla, were killed at a wedding party when Al-Qaeda bombed the Grand Hyatt in Amman, Jordan. As the champion of the series since its inception, his tragic death was a blow for the future of the franchise. This, coupled with Dimension Film execs realising (maybe) the error of their ways with Halloween Resurrection, looked set to see the end of the Halloween films. However, following a trend of remaking old horror films from the Seventies and Eighties such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Black Christmas, Dawn of the Dead, The Hills Have Eyes, The Amityville Horror and When A Stranger Calls, producers recognised that Halloween was still a marketable name and decided to reboot/re-imagine/remake/reconceptualise John Carpenter’s landmark slasher.

It came as little surprise then when he announced his involvement with the remake of Halloween, and his intention to explore the childhood of its antagonist Michael Myers. Villains have always been the more fleshed out characters in Zombie’s films – he shows more of an interest in them than his ‘heroes.’ This aspect of probing Myers’ fractured mindset and background is the basis of the remake and perhaps it’s most original and compelling segment before it eventually descends into extreme violence and tensionless bloodletting.

Myers is presented as a sensitive, shy child with worryingly violent tendencies (he kills small animals, usually a sign of psychopathic personality disorder). His mother works as an exotic dancer to support her family, his sister has no time for him, and his tyrannical step-father abuses the family, physically and emotionally. In his presentation of Myers’ dysfunctional family, Zombie seems to be saying that though many people have been dealt a shit deal in life – it is only a few whose inability to deal with it and see beyond it that become inherently corrupted. That’s not to say that Halloween is an insightful and nuanced deconstruction of human psychology. It isn’t – far from it in fact, as sometimes it feels one-dimensional, even caricaturist – but it’s all carried off with such besmirched aplomb, Zombie makes it work. It’s pop psychology by numbers, but in the context of a Rob Zombie film, it further showcases the director’s willingness to explore sleazy, disturbed characters and the sordid surroundings they exist in.

As the young Michael Myers, Daeg Faerch brings a quiet intensity to the fledgling killer. As his put-upon mother, Sherri Moon Zombie's sympathetic performance highlights Deborah Myers’ down-beaten resignation and begrudging acceptance of her life - she does what she can to hold everything together, but she's always up against it. Malcolm McDowell is an interesting Dr Loomis, though he isn’t given much to do except spout Donald Pleasence-isms about Myers’ inhumanity and devilish black eyes, and to say Tyler Mane’s adult incarnation of Myers is an imposing, formidable sight is an obvious understatement. Gone are Carpenter’s subtle placements of the killer at the edge of the screen, and in evidence are Zombie’s presentations of Myers as a barraging, relentlessly brutal bulldozer.

While Zombie’s Halloween has its flaws, it still manages to exemplify the directorial showmanship of Zombie and mark him as an interesting filmmaker with unique vision. His Halloween might not do as much justice to Carpenter’s original as many would have hoped, but as a Rob Zombie film, it follows on perfectly from the likes of The Devil’s Rejects, in the director’s ongoing obsession with submergence in the seedy underbelly of American society.