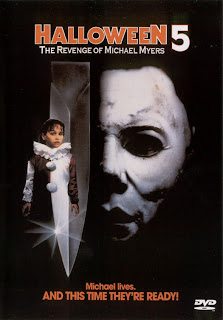

Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers

1989

Dir. Dominique Othenin-Girard

One year after surviving her blood-drenched ordeal at the hands of her murderous uncle, psychotic killer Michael Myers, young Jamie has been committed to the Haddonfield Children’s Clinic, rendered mute from her traumatic experiences. The presumed dead, though actually just comatose Myers, awakens and returns to finish what he started. Meanwhile, Jamie develops a strange psychic link with him, which her psychiatrist, Dr Loomis, plans to exploit in a bid to stop Myers once and for all. But wait! Who is that mysterious man in black who also stalks the streets of Haddonfield? And why is he so seemingly interested in Jamie and her uncle?

Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers was successful enough to lead producer Moustapha Akkad to believe it warranted a follow up. Initial drafts of Halloween 5’s script dutifully acknowledged the ending of Part 4 in which Jamie was established as Michael Myers’ murderous successor, however producers rejected this notion perhaps worried that another Myers-less entry in the series (a la Halloween III) wouldn’t be favoured by fans. Despite the story focusing once again on Myers’ attempts to murderlise his young niece, Halloween 5 went on to become the least successful film in the series – earning even less at the box office than Part III. Reprising their roles from the previous film were Donald Pleasence (who favoured the script featuring Jamie as a killer), Danielle Harris as Jamie, Ellie Cornell as Rachel, and Beau Starr as Sheriff Ben Meeker.

Halloween 5 begins with a recap of Part 4’s last scenes in which murderlising maniac Michael Myers was ran over repeatedly by Rachel and Jamie and then blasted into a nearby mineshaft by the police. Just to make sure he really was dead, they also tossed in a grenade to blow him up. Hey, you can never be too sure when it comes to these slasher villains – especially if their franchises are even remotely lucrative. And the Halloween series, despite rampaging in circles of ever-decreasing quality, was still pretty popular, so it turns out that Myers wasn’t finished off by the explosion after all. Shocker. Escaping from the mine and being carried away by a nearby river, he winds up stumbling upon the shack of an old hermit before promptly falling into a coma. Waking up a year later, just in time for Halloween, he murders the hospitable hermit and stomps off to Haddonfield in search of Jamie again.

The ending of Part 4 – which set up Jamie as Myers’ successor – isn’t continued here. Turns out she didn’t kill her stepmother as suggested, she only stabbed her and was soon hospitalised. Logic and continuity were never really the strong points of slasher sequels anyway. As with Part 4, we’re also introduced to a new slew of knife fodder in the form of Rachel’s friends, and Swiss director Othenin-Girard attempts to mimic John Carpenter’s methods of building tension through the use of false alarms and long bouts of suggestive menace as Myers stalkses and slasheses his way through the teen population of Haddonfield. The false alarms become tedious very quickly, and the moments of violence are separated by long periods of utter tedium in which bland and annoying characters play practical jokes, have sex in a barn, spout inane drivel and wander off into darkened corners to check out strange noises. Did I mention these scenes were tedious beyond belief and these characters the most vapid, hollow and depressing ever stalked in a slasher movie? Even Loomis doesn’t fare well in Part 5. He begins to pop up in scenes as unexpectedly as Myers does and acts completely out of character. Sure, he’s been driven to the brink by his inability to stop his former patient, but that he actually puts Jamie’s life at risk in an attempt to trap Myers doesn’t ring true. His usual rambling jargon about Myers being ‘evil incarnate’ consistently highlights the ‘rage’ that drives him and how Jamie may be the only way to quell it. Despite being rendered mute for the first half of the film, Danielle Harris, as the long-suffering Jamie, pretty much carries the film and commands attention in all the scenes she appears in.

As the plot shambles on in ever bland stops and starts, the only thing that causes tension is that the life of a young child is constantly put in jeopardy by the ineptitude of those responsible for her. And even then it isn’t really tension experienced, but frustration and eventually boredom. One genuinely tense scene occurs when Myers pursues Jamie through his old house and she takes refuge in a laundry chute. Another scene that exhibits an uncanny creepiness occurs when Tina (Wendy Kaplan) is picked up in a car by Myers – sporting a new mask - whom she believes is her boyfriend dressed up for the Halloween party. An odd sense of humour – both inappropriate (the bumbling cop duo) and strangely reflexive (when Spitz pretends to be Myers in a practical joke on the cops and 'attacks' Samantha, Tina screams for him to "Take me, but spare my friend! She's a virgin!") randomly perforates an otherwise gloomily serious tone and further reduces any hint of suspense that could have been mustered.

Despite the lack of tension and increasing tedium, the one thing that Halloween 5 does get right is atmosphere. The film possesses a strangely gothic ambience – from the early scene in which Myers encounters a wood-dwelling hermit who nurses him back to health (echoing a similar scene in Mary Shelley’s 'Frankenstein' and the scene in James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein in which ‘the monster’ receives hospitality before killing his host) to the gothic trimmings of the Myers’ house (with its turrets, candle-lit corridors and high arched windows) to the pilfering of a plot device evident in Bram Stoker’s 'Dracula' involving psychic-links between heroine and villain. The lighting and sound design is also atmospherically effective and Othenin-Girard injects a strange European style into proceedings. Stepping away from the eerie blue lighting of prior instalments this one is bathed in blacks, reds and gold. The creepy sound design highlights every creaking floorboard, gust of howling wind and echo of potential menace. Othenin-Girard also deploys more use of POV camerawork which harks back to the original film.

Also present are a number of interesting elements that quiver tantalisingly amongst the deluge. As in Parts II and 4, so too does Part 5 feature several scenes in which various people try to reason with Myers – in this case Loomis and Jamie respectively. A close-up shot of his eye reveals Myers to shed a tear, too. Also introduced in this film, though never elaborated on (until Part 6) is the notion that Michael Myers may be part of a strange cult – he and the Man in Black who creeps around for most of the film only to really feature significantly in the climax, are revealed to have the same strange runic symbol tattooed on their arms.

Utterly devoid of suspense and momentum, Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers marks a real low point in the series. Were it not for the embarrassment that is Halloween: Resurrection, it would have marked the nadir of the series. The few intriguing aspects it contains were seemingly only designed to be followed up on in further instalments.

Dir. Dominique Othenin-Girard

One year after surviving her blood-drenched ordeal at the hands of her murderous uncle, psychotic killer Michael Myers, young Jamie has been committed to the Haddonfield Children’s Clinic, rendered mute from her traumatic experiences. The presumed dead, though actually just comatose Myers, awakens and returns to finish what he started. Meanwhile, Jamie develops a strange psychic link with him, which her psychiatrist, Dr Loomis, plans to exploit in a bid to stop Myers once and for all. But wait! Who is that mysterious man in black who also stalks the streets of Haddonfield? And why is he so seemingly interested in Jamie and her uncle?

Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers was successful enough to lead producer Moustapha Akkad to believe it warranted a follow up. Initial drafts of Halloween 5’s script dutifully acknowledged the ending of Part 4 in which Jamie was established as Michael Myers’ murderous successor, however producers rejected this notion perhaps worried that another Myers-less entry in the series (a la Halloween III) wouldn’t be favoured by fans. Despite the story focusing once again on Myers’ attempts to murderlise his young niece, Halloween 5 went on to become the least successful film in the series – earning even less at the box office than Part III. Reprising their roles from the previous film were Donald Pleasence (who favoured the script featuring Jamie as a killer), Danielle Harris as Jamie, Ellie Cornell as Rachel, and Beau Starr as Sheriff Ben Meeker.

Halloween 5 begins with a recap of Part 4’s last scenes in which murderlising maniac Michael Myers was ran over repeatedly by Rachel and Jamie and then blasted into a nearby mineshaft by the police. Just to make sure he really was dead, they also tossed in a grenade to blow him up. Hey, you can never be too sure when it comes to these slasher villains – especially if their franchises are even remotely lucrative. And the Halloween series, despite rampaging in circles of ever-decreasing quality, was still pretty popular, so it turns out that Myers wasn’t finished off by the explosion after all. Shocker. Escaping from the mine and being carried away by a nearby river, he winds up stumbling upon the shack of an old hermit before promptly falling into a coma. Waking up a year later, just in time for Halloween, he murders the hospitable hermit and stomps off to Haddonfield in search of Jamie again.

The ending of Part 4 – which set up Jamie as Myers’ successor – isn’t continued here. Turns out she didn’t kill her stepmother as suggested, she only stabbed her and was soon hospitalised. Logic and continuity were never really the strong points of slasher sequels anyway. As with Part 4, we’re also introduced to a new slew of knife fodder in the form of Rachel’s friends, and Swiss director Othenin-Girard attempts to mimic John Carpenter’s methods of building tension through the use of false alarms and long bouts of suggestive menace as Myers stalkses and slasheses his way through the teen population of Haddonfield. The false alarms become tedious very quickly, and the moments of violence are separated by long periods of utter tedium in which bland and annoying characters play practical jokes, have sex in a barn, spout inane drivel and wander off into darkened corners to check out strange noises. Did I mention these scenes were tedious beyond belief and these characters the most vapid, hollow and depressing ever stalked in a slasher movie? Even Loomis doesn’t fare well in Part 5. He begins to pop up in scenes as unexpectedly as Myers does and acts completely out of character. Sure, he’s been driven to the brink by his inability to stop his former patient, but that he actually puts Jamie’s life at risk in an attempt to trap Myers doesn’t ring true. His usual rambling jargon about Myers being ‘evil incarnate’ consistently highlights the ‘rage’ that drives him and how Jamie may be the only way to quell it. Despite being rendered mute for the first half of the film, Danielle Harris, as the long-suffering Jamie, pretty much carries the film and commands attention in all the scenes she appears in.

As the plot shambles on in ever bland stops and starts, the only thing that causes tension is that the life of a young child is constantly put in jeopardy by the ineptitude of those responsible for her. And even then it isn’t really tension experienced, but frustration and eventually boredom. One genuinely tense scene occurs when Myers pursues Jamie through his old house and she takes refuge in a laundry chute. Another scene that exhibits an uncanny creepiness occurs when Tina (Wendy Kaplan) is picked up in a car by Myers – sporting a new mask - whom she believes is her boyfriend dressed up for the Halloween party. An odd sense of humour – both inappropriate (the bumbling cop duo) and strangely reflexive (when Spitz pretends to be Myers in a practical joke on the cops and 'attacks' Samantha, Tina screams for him to "Take me, but spare my friend! She's a virgin!") randomly perforates an otherwise gloomily serious tone and further reduces any hint of suspense that could have been mustered.

Despite the lack of tension and increasing tedium, the one thing that Halloween 5 does get right is atmosphere. The film possesses a strangely gothic ambience – from the early scene in which Myers encounters a wood-dwelling hermit who nurses him back to health (echoing a similar scene in Mary Shelley’s 'Frankenstein' and the scene in James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein in which ‘the monster’ receives hospitality before killing his host) to the gothic trimmings of the Myers’ house (with its turrets, candle-lit corridors and high arched windows) to the pilfering of a plot device evident in Bram Stoker’s 'Dracula' involving psychic-links between heroine and villain. The lighting and sound design is also atmospherically effective and Othenin-Girard injects a strange European style into proceedings. Stepping away from the eerie blue lighting of prior instalments this one is bathed in blacks, reds and gold. The creepy sound design highlights every creaking floorboard, gust of howling wind and echo of potential menace. Othenin-Girard also deploys more use of POV camerawork which harks back to the original film.

Also present are a number of interesting elements that quiver tantalisingly amongst the deluge. As in Parts II and 4, so too does Part 5 feature several scenes in which various people try to reason with Myers – in this case Loomis and Jamie respectively. A close-up shot of his eye reveals Myers to shed a tear, too. Also introduced in this film, though never elaborated on (until Part 6) is the notion that Michael Myers may be part of a strange cult – he and the Man in Black who creeps around for most of the film only to really feature significantly in the climax, are revealed to have the same strange runic symbol tattooed on their arms.

Utterly devoid of suspense and momentum, Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers marks a real low point in the series. Were it not for the embarrassment that is Halloween: Resurrection, it would have marked the nadir of the series. The few intriguing aspects it contains were seemingly only designed to be followed up on in further instalments.