When I began to flesh out my thoughts and hastily scribbled notes on The Black Cat, I ended up spewing forth a tangent about why I find Lucio Fulci’s film work so disturbing, horrifying and repellent. Below is said tangent, and the review of The Black Cat (tangent free) can be found here.

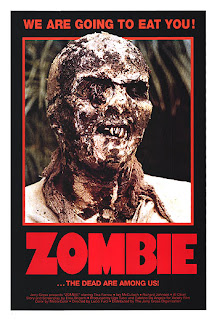

Of the countless schlocky, ultra-violent, exploitation-laden fare this writer has watched over the years - and the plethora of disturbing, mind-numbingly deplorable and brain-botheringly wretched imagery I’ve witnessed as a result of watching such fare - one filmmaker and his work stands apart from the others when it comes to creating genuinely upsetting, avert-your-gaze-from-the-screen-in-disgust moments. Lucio Fulci is a director most fans of horror cinema will be familiar with. Heck, many of them will even own some of his work on DVD or something called VHS. My own experience of watching Fulci’s work is quite limited. I find his films to be disturbing, disgusting and weirdly depressing. The more I think about this though, and the more I consider my reactions when watching his films, the closer I have come to the conclusion that Lucio Fulci is perhaps one of the most effective directors who ever worked in the horror genre. His work is rare in that, even though I find it shoddy and unpleasant, it still, somehow, wields the power to bother and upset me. It actually scuttles under my skin, and there are images I can never un-see. That his work is able to disturb me so much – a hardened horror fanatic – must surely speak volumes about his effectiveness as a horror film-maker?

Of the countless schlocky, ultra-violent, exploitation-laden fare this writer has watched over the years - and the plethora of disturbing, mind-numbingly deplorable and brain-botheringly wretched imagery I’ve witnessed as a result of watching such fare - one filmmaker and his work stands apart from the others when it comes to creating genuinely upsetting, avert-your-gaze-from-the-screen-in-disgust moments. Lucio Fulci is a director most fans of horror cinema will be familiar with. Heck, many of them will even own some of his work on DVD or something called VHS. My own experience of watching Fulci’s work is quite limited. I find his films to be disturbing, disgusting and weirdly depressing. The more I think about this though, and the more I consider my reactions when watching his films, the closer I have come to the conclusion that Lucio Fulci is perhaps one of the most effective directors who ever worked in the horror genre. His work is rare in that, even though I find it shoddy and unpleasant, it still, somehow, wields the power to bother and upset me. It actually scuttles under my skin, and there are images I can never un-see. That his work is able to disturb me so much – a hardened horror fanatic – must surely speak volumes about his effectiveness as a horror film-maker?

Fulci is one of those directors that you can’t rely on. He isn’t safe. Anything can happen in his sickeningly nightmarish and progressively downbeat narratives - and it usually does: to petrified characters who exist solely to die horribly. His feeble characters have lost the ability to think reasonably, or, you know, just move the fuck out of the way of danger. The logic of nightmares comes into play throughout his work, rendering it frustrating, suspenseful and thoroughly perturbing. No matter what his characters do, or don’t do as the case usually is, they still die. Gruesomely. They stand rooted to the spot, petrified, or flail around weakly, usually while on fire, or cornered by the living dead, in pathetic throes of agony, powerless to fight for their lives. Resistance is futile. These moments are the stuff of nightmares – and when the nightmare always works against you – and you experience that loss of control – you know it’s a powerful one. And yet, even as wispily drawn as these characters are, their plight still bothers me. Fulci’s positively misanthropic attitude is one of the most prominent and uneasy characteristics of his horror films.

This aspect of his work boasts a queasy power, and it’s within this juxtaposing dichotomy of ‘disturbing and affecting’ and ‘crass and trashy’, his effectiveness as a horror director lies. There’s just something about it that still has the power to really disturb, despite the sham artifice of it all.

When one thinks about the term ‘Horror’ and what it literally means – according to the definition in the Oxford Dictionary it is ‘an intense feeling of fear, shock, or disgust’ – the prominent emotions it refers to centre around revulsion and disgust; gut reactions to visceral information. Horror dignitaries such as Boris Karloff and Val Lewton knew this all too well and actually went as far as referring to the films they made as ‘terror’ films, or ‘chillers’, because the desired reaction they sought to illicit from viewers was not to disgust or revolt, but to terrify. Stephen King discusses the difference between ‘horror’ (revulsion, disgust) and ‘terror’ (extreme fear) in his non-fiction meditation on the genre, 'Danse Macabre.' Therefore, it safe to say that Fulci’s brand of cinema is firmly rooted in ‘horror’; these are exactly the reactions he wishes to generate.

As stylish as some of his films can be, the violence is depicted unflinchingly, graphically, sadistically. Whether it’s images of characters vomiting up their own guts; being flayed and whipped with chains; having their eye gouged out, slowly, on a large splinter of wood; being beheaded in the basement of a house by the cemetery; devoured by giant spiders; having their heads drilled open… What? Enough? Yeah, I think I’ll stop. My point, and I did have one, is that once you see a Fulci film, you can’t un-see it. Those images will ingrain themselves in your pink-matter forever. In all their preposterous, alarming, silly, shocking, queasy, frustrating and disturbing glory. The sickening atmospheres, pregnant with decay and stinking uneasiness, that pervade Fulci’s movies are unforgettable, regardless of how they are conveyed.

As stylish as some of his films can be, the violence is depicted unflinchingly, graphically, sadistically. Whether it’s images of characters vomiting up their own guts; being flayed and whipped with chains; having their eye gouged out, slowly, on a large splinter of wood; being beheaded in the basement of a house by the cemetery; devoured by giant spiders; having their heads drilled open… What? Enough? Yeah, I think I’ll stop. My point, and I did have one, is that once you see a Fulci film, you can’t un-see it. Those images will ingrain themselves in your pink-matter forever. In all their preposterous, alarming, silly, shocking, queasy, frustrating and disturbing glory. The sickening atmospheres, pregnant with decay and stinking uneasiness, that pervade Fulci’s movies are unforgettable, regardless of how they are conveyed.

Such moments typify his work. They highlight and exemplify his exploration of what will make his audience look away, to feel repulsed. It is this William Burroughs-esque approach to his material – the refusal to censor the most horrific, sickeningly twisted stuff he can come up with - that makes his work and the horrid images contained therein, so memorable. The images he creates and then allows his camera to gaze at in long, lingering shots are disgusting and primal, yet we cannot tear our eyes from them, we only feel compelled to look at them. Throughout his long and uneven career Fulci delved into our deepest, most basic fears, dredged them up, embalmed them in nightmarishly nihilistic logic, heaped on the decomposing, rotting flesh, all the while ripping open flesh and sloshing the insides across the screen of his uneven, yet genuinely disturbing cinema.