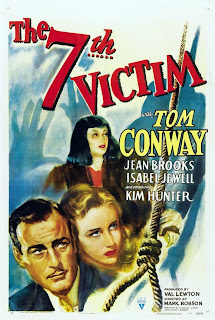

1943

Dir. Mark Robson

A young woman frantically searches New York for her missing sister, only to discover her sibling was involved in a mysterious Satanic cult and now owes her life to them.

Combining elements of horror and noir, The Seventh Victim is a sombre, atmospheric and haunting film preoccupied with notions of death, loneliness, suicide and despair. Under the guidance of producer Val Lewton, director Robson conjures an atmosphere of hopelessness and oppression, heightened by shadowy visuals and an unshakable air of paranoia. Rife with a dark and morbid romanticism, the film sleekly unfurls and proves utterly gripping; all the way to its breathtakingly bleak denouement. Purportedly Lewton’s most personal work, The Seventh Victim is set in Greenwich Village and populated by academics, poets and writers who frequent trendy cafes and bohemian apartments. As well as the opening quote which establishes the downbeat tone – “I come to Death and Death meets me as fast and all my pleasures are as yesterday” - the film brims with references to poetry and literature, such as the name of Mary’s headmistress (Miss Lowood - the name of the school Jane Erye attended), and the name of the restaurant (Dante’s) above which Jacqueline rents a room in which to contemplate her dark fate.

The original screenplay, written by Lewton and DeWitt Bodeen, centred on a young woman who realises she is to be the seventh victim of a murderer. Set in the vast sprawling landscapes of the southern Californian oil fields, Lewton soon decided to scrap that treatment, opting to write a story about a Satanic cult and the woman who is doomed to die for betraying them. The Seventh Victim was also set to be the producer’s first A picture, as Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie had been so successful. His insistence that Mark Robson direct was not taken well by executives who believed he was too inexperienced to handle an A budgeted project. Lewton’s loyalty to his former editor persisted however, and the film’s budget was eventually cut back to that of a B movie. This meant certain scenes had to be re-written and even edited out of the final cut, resulting in a slightly muddled narrative with the occasional plot hole. Perhaps Lewton’s disappointment is what fuelled the overwhelmingly bleak outlook of the film, the title and plot of which slyly subvert the number usually associated with good luck.

Deftly entwining elements of noir with horror, much as Lewton and co did with Cat People and The Leopard Man, the film is populated with tragic, flawed characters. Jacqueline (Jean Brooks), prior to the events depicted in the film, had an unquenchable thirst for life and living. It was her desire for new experiences that led to her doomful encounter with the cult. Her crime against them was growing bored; she is essentially damned by her own intrinsically capricious nature. That so many of the characters are trying in vain to help Jacqueline, who is so obviously resigned to her fate, adds to the sheen of futility and hopelessness that enrobes the film. Another element that contributes to the tragic feel is actress Jean Brooks’ own heart-rending personal life. After starring in a number of films, she eventually retired from acting and disappeared from public life before dying of problems stemming from alcoholism. Her performance in The Seventh Victim is startlingly effective. While she portrayed one of Lewton’s typically strong female characters (Kiki) in The Leopard Man, she delivers a compelling performance as troubled Jacqueline; at once enigmatic and engaging, she steals every scene as the raven-haired woman. When Jacqueline encounters her terminally ill neighbour Mimi (Elizabeth Russell) preparing to go out for the evening to make the most of her limited time, the contrast between the two characters and their attitudes to death is incredibly powerful in the most understated way.

Even minor characters, such as the teacher who beseeches Mary (Kim Hunter) not to come back to the school, but to find the courage to live life, are surrounded by an aura of sadness. The members of the cult are also interestingly drawn. Mainly middle class types, bored and in search of new experiences, the Palladists are presented as ordinary people who actually like Jacqueline and don’t really want to kill her; their abstinence from violence is what pushes them to try to force her to take her own life. Even this is initially unsuccessful. She is defiant and determined, but eventually succumbs to the stifling oppression of her predicament. This presentation of the members of a satanic cult as everyday, mundane people would be echoed by Ira Levin in his novel Rosemary’s Baby, eventually adapted for the screen by Roman Polanski. There’s a sense that there is no clear cut villain here. The members of the cult are as confined by the laws that govern their beliefs as Jacqueline is. This adds to the strangely tragic air that lingers throughout the film, and harks back to The Leopard Man’s central notion that we are governed by forces we have no control over. Eventually, a more sinister side of the cult is revealed when they hire an assassin to kill Jacqueline if she won’t take her own life. This is what pushes Jacqueline to act; she is determined that no one but she will end her life and, no matter how futile, she desperately attempts to maintain control, evoking all manner of ideas about free will, agency and self determination.

“Your sister had a feeling about life – that it wasn’t worth living unless one could end it.”

A number of scenes stand out, particularly when Mary and her private investigator, Irving August (Lou Lubin), sneak into Jacqueline’s old cosmetics factory to look for clues to her whereabouts, only for August to disappear down a dark, shadowy corridor and emerge with a knife in his back. The scene that follows, in which Mary flees into the New York underground and she sees two men disposing of August’s body by pretending he’s a drunk companion in need of chaperoning is also wonderfully executed. Later, in a scene pre-empting Psycho, Mary is menaced in the shower when one of the members of the cult comes to warn her to stop looking for Jacqueline. The scene is incredibly creepy; shoot from Mary’s point of view, naked and vulnerable, she sees the silhouette of the woman through the shower curtain; stark and domineering.

The Seventh Victim also boasts one of the best ‘Lewton walks.’ When Jacqueline tries to walk home alone after being allowed to leave the Palladists’ meeting, she is stalked by a hit man who emerges from the darkness of a doorway she passes on an eerily deserted street. This scene echoes earlier Lewton walks such as when Irena stalks Alice through Central Park in Cat People; when Betty and Jessica make their way through moonlit fields to visit a witch doctor in I Walked with a Zombie; and when Teresa is made to trek across the outskirts of town to run an errand for her mother in The Leopard Man. Shadowy lighting, smooth tracking shots and mounting tension combine to create one of the best stalking scenes of any Lewton production.

Tom Conway appears as Dr Judd, the psychiatrist who treats Irena Reed in Lewton’s first horror production, Cat People. Do the stories of Cat People and The Seventh Victim run in tandem with each other? Or does The Seventh Victim inhabit a space in time that precedes events in Cat People? Interestingly, Judd refers to the tragic fate of a young woman he’s been treating – is this Irena? While no definite answer is provided, his chillingly suave presence provides an interesting link to the world in which Cat People plays out and it seems the films exist in the same universe.

The Seventh Victim is an uncompromisingly downbeat film, at odds with the usual ‘good overcomes evil’ outlook of other war time horror flicks, and it emerges as a minor masterpiece as interestingly flawed as the characters who inhabit its quietly desperate story. That it rewards repeated viewing is testament to its subtle nuances and masterful execution.

Dir. Mark Robson

A young woman frantically searches New York for her missing sister, only to discover her sibling was involved in a mysterious Satanic cult and now owes her life to them.

Combining elements of horror and noir, The Seventh Victim is a sombre, atmospheric and haunting film preoccupied with notions of death, loneliness, suicide and despair. Under the guidance of producer Val Lewton, director Robson conjures an atmosphere of hopelessness and oppression, heightened by shadowy visuals and an unshakable air of paranoia. Rife with a dark and morbid romanticism, the film sleekly unfurls and proves utterly gripping; all the way to its breathtakingly bleak denouement. Purportedly Lewton’s most personal work, The Seventh Victim is set in Greenwich Village and populated by academics, poets and writers who frequent trendy cafes and bohemian apartments. As well as the opening quote which establishes the downbeat tone – “I come to Death and Death meets me as fast and all my pleasures are as yesterday” - the film brims with references to poetry and literature, such as the name of Mary’s headmistress (Miss Lowood - the name of the school Jane Erye attended), and the name of the restaurant (Dante’s) above which Jacqueline rents a room in which to contemplate her dark fate.

The original screenplay, written by Lewton and DeWitt Bodeen, centred on a young woman who realises she is to be the seventh victim of a murderer. Set in the vast sprawling landscapes of the southern Californian oil fields, Lewton soon decided to scrap that treatment, opting to write a story about a Satanic cult and the woman who is doomed to die for betraying them. The Seventh Victim was also set to be the producer’s first A picture, as Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie had been so successful. His insistence that Mark Robson direct was not taken well by executives who believed he was too inexperienced to handle an A budgeted project. Lewton’s loyalty to his former editor persisted however, and the film’s budget was eventually cut back to that of a B movie. This meant certain scenes had to be re-written and even edited out of the final cut, resulting in a slightly muddled narrative with the occasional plot hole. Perhaps Lewton’s disappointment is what fuelled the overwhelmingly bleak outlook of the film, the title and plot of which slyly subvert the number usually associated with good luck.

Deftly entwining elements of noir with horror, much as Lewton and co did with Cat People and The Leopard Man, the film is populated with tragic, flawed characters. Jacqueline (Jean Brooks), prior to the events depicted in the film, had an unquenchable thirst for life and living. It was her desire for new experiences that led to her doomful encounter with the cult. Her crime against them was growing bored; she is essentially damned by her own intrinsically capricious nature. That so many of the characters are trying in vain to help Jacqueline, who is so obviously resigned to her fate, adds to the sheen of futility and hopelessness that enrobes the film. Another element that contributes to the tragic feel is actress Jean Brooks’ own heart-rending personal life. After starring in a number of films, she eventually retired from acting and disappeared from public life before dying of problems stemming from alcoholism. Her performance in The Seventh Victim is startlingly effective. While she portrayed one of Lewton’s typically strong female characters (Kiki) in The Leopard Man, she delivers a compelling performance as troubled Jacqueline; at once enigmatic and engaging, she steals every scene as the raven-haired woman. When Jacqueline encounters her terminally ill neighbour Mimi (Elizabeth Russell) preparing to go out for the evening to make the most of her limited time, the contrast between the two characters and their attitudes to death is incredibly powerful in the most understated way.

Even minor characters, such as the teacher who beseeches Mary (Kim Hunter) not to come back to the school, but to find the courage to live life, are surrounded by an aura of sadness. The members of the cult are also interestingly drawn. Mainly middle class types, bored and in search of new experiences, the Palladists are presented as ordinary people who actually like Jacqueline and don’t really want to kill her; their abstinence from violence is what pushes them to try to force her to take her own life. Even this is initially unsuccessful. She is defiant and determined, but eventually succumbs to the stifling oppression of her predicament. This presentation of the members of a satanic cult as everyday, mundane people would be echoed by Ira Levin in his novel Rosemary’s Baby, eventually adapted for the screen by Roman Polanski. There’s a sense that there is no clear cut villain here. The members of the cult are as confined by the laws that govern their beliefs as Jacqueline is. This adds to the strangely tragic air that lingers throughout the film, and harks back to The Leopard Man’s central notion that we are governed by forces we have no control over. Eventually, a more sinister side of the cult is revealed when they hire an assassin to kill Jacqueline if she won’t take her own life. This is what pushes Jacqueline to act; she is determined that no one but she will end her life and, no matter how futile, she desperately attempts to maintain control, evoking all manner of ideas about free will, agency and self determination.

“Your sister had a feeling about life – that it wasn’t worth living unless one could end it.”

A number of scenes stand out, particularly when Mary and her private investigator, Irving August (Lou Lubin), sneak into Jacqueline’s old cosmetics factory to look for clues to her whereabouts, only for August to disappear down a dark, shadowy corridor and emerge with a knife in his back. The scene that follows, in which Mary flees into the New York underground and she sees two men disposing of August’s body by pretending he’s a drunk companion in need of chaperoning is also wonderfully executed. Later, in a scene pre-empting Psycho, Mary is menaced in the shower when one of the members of the cult comes to warn her to stop looking for Jacqueline. The scene is incredibly creepy; shoot from Mary’s point of view, naked and vulnerable, she sees the silhouette of the woman through the shower curtain; stark and domineering.

The Seventh Victim also boasts one of the best ‘Lewton walks.’ When Jacqueline tries to walk home alone after being allowed to leave the Palladists’ meeting, she is stalked by a hit man who emerges from the darkness of a doorway she passes on an eerily deserted street. This scene echoes earlier Lewton walks such as when Irena stalks Alice through Central Park in Cat People; when Betty and Jessica make their way through moonlit fields to visit a witch doctor in I Walked with a Zombie; and when Teresa is made to trek across the outskirts of town to run an errand for her mother in The Leopard Man. Shadowy lighting, smooth tracking shots and mounting tension combine to create one of the best stalking scenes of any Lewton production.

Tom Conway appears as Dr Judd, the psychiatrist who treats Irena Reed in Lewton’s first horror production, Cat People. Do the stories of Cat People and The Seventh Victim run in tandem with each other? Or does The Seventh Victim inhabit a space in time that precedes events in Cat People? Interestingly, Judd refers to the tragic fate of a young woman he’s been treating – is this Irena? While no definite answer is provided, his chillingly suave presence provides an interesting link to the world in which Cat People plays out and it seems the films exist in the same universe.

The Seventh Victim is an uncompromisingly downbeat film, at odds with the usual ‘good overcomes evil’ outlook of other war time horror flicks, and it emerges as a minor masterpiece as interestingly flawed as the characters who inhabit its quietly desperate story. That it rewards repeated viewing is testament to its subtle nuances and masterful execution.