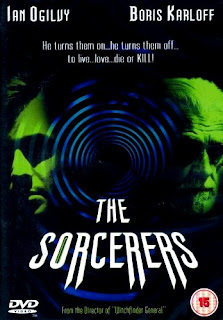

The Sorcerers

1967

Dir. Michael Reeves

An ailing scientist and his wife create a device that enables them to control the mind of a young man and share the sensations of his physical experiences. It isn’t long though before the wife, drunk on power and obsessed with experiencing new things, begins to indulge her increasingly perverse desires, including murder.

Reeves’ penultimate film is a curiously irresistible blend of horror and sci-fi, filtered through a cynical snapshot of swinging sixties London – and the moral vacuum of the characters – spiced up with various ‘mad scientist’ tropes. While it may be overshadowed by his last film The Witchfinder General, The Sorcerers exhibits as idiosyncratic and bleak an outlook on the corruptible nature of humanity as the Vincent Price starring classic. Both films peer into the depths of what causes normal people to do corrupt, despicable things, and due to its then-contemporary setting, The Sorcerers makes an especially powerful impact in this regard. As the initially benign old couple begin to wade out of their depth the longer their experiment continues, the more things get out of hand. The Sorcerers arguably acts as a sly metaphor for cinema and the experience it provides to its audience, with Dr Monserrat and his wife Estelle (Boris Karloff and Catherine Lacey), much like the detached viewer, abandoning their own lives and momentarily escaping into a new world experiencing sensations through someone else.

While Mike (Ian Ogilvy) isn’t a particularly sympathetic character, that he is forced to carry out such wicked actions against, and even oblivious, to his own will, generates a certain degree of sympathy for him, and poses provocative questions about free will and agency. When Dr Monserrat initially created the device, it was with the intention of providing certain experiences to those no longer capable of such things; such as the poor and the elderly. The flipside of course is that the person who is actually living the experiences on behalf of the mind-controller, no longer has any control or free will. Their life is not their own. Both the Monserrats and Mike discard their responsibilities to pursue selfish needs. Mike constantly abandons his friends without a thought for their feelings, and Estelle increasingly cares less about the consequences of her own selfish actions.

While Lacey and Karloff are relegated to their small flat for the majority of the film, sitting around a table as they experience life through Mike and exchanging rather heavy-handed dialogue, they still prove compelling to watch. In lesser hands, these moments would become pantomime. Boris Karloff actually plays against type here and he imbues Dr Monserrat with a quiet dignity. Far from the mad scientist he initially appears to be, he forms the moral conscience of the film, helplessly watching as Estelle delves deeper into her increasingly dark and diabolical instincts and living out her depraved fantasies through Mike. Catherine Lacey delivers a quietly intense performance, expertly conveying Estelle's spiral into obsession and moral decay. Generational conflict is evident throughout proceedings, with the Monserrats viewing young people with disdain and eventually as mere commodities through which they can live out their own desires.

Dir. Michael Reeves

An ailing scientist and his wife create a device that enables them to control the mind of a young man and share the sensations of his physical experiences. It isn’t long though before the wife, drunk on power and obsessed with experiencing new things, begins to indulge her increasingly perverse desires, including murder.

Reeves’ penultimate film is a curiously irresistible blend of horror and sci-fi, filtered through a cynical snapshot of swinging sixties London – and the moral vacuum of the characters – spiced up with various ‘mad scientist’ tropes. While it may be overshadowed by his last film The Witchfinder General, The Sorcerers exhibits as idiosyncratic and bleak an outlook on the corruptible nature of humanity as the Vincent Price starring classic. Both films peer into the depths of what causes normal people to do corrupt, despicable things, and due to its then-contemporary setting, The Sorcerers makes an especially powerful impact in this regard. As the initially benign old couple begin to wade out of their depth the longer their experiment continues, the more things get out of hand. The Sorcerers arguably acts as a sly metaphor for cinema and the experience it provides to its audience, with Dr Monserrat and his wife Estelle (Boris Karloff and Catherine Lacey), much like the detached viewer, abandoning their own lives and momentarily escaping into a new world experiencing sensations through someone else.

While Mike (Ian Ogilvy) isn’t a particularly sympathetic character, that he is forced to carry out such wicked actions against, and even oblivious, to his own will, generates a certain degree of sympathy for him, and poses provocative questions about free will and agency. When Dr Monserrat initially created the device, it was with the intention of providing certain experiences to those no longer capable of such things; such as the poor and the elderly. The flipside of course is that the person who is actually living the experiences on behalf of the mind-controller, no longer has any control or free will. Their life is not their own. Both the Monserrats and Mike discard their responsibilities to pursue selfish needs. Mike constantly abandons his friends without a thought for their feelings, and Estelle increasingly cares less about the consequences of her own selfish actions.

While Lacey and Karloff are relegated to their small flat for the majority of the film, sitting around a table as they experience life through Mike and exchanging rather heavy-handed dialogue, they still prove compelling to watch. In lesser hands, these moments would become pantomime. Boris Karloff actually plays against type here and he imbues Dr Monserrat with a quiet dignity. Far from the mad scientist he initially appears to be, he forms the moral conscience of the film, helplessly watching as Estelle delves deeper into her increasingly dark and diabolical instincts and living out her depraved fantasies through Mike. Catherine Lacey delivers a quietly intense performance, expertly conveying Estelle's spiral into obsession and moral decay. Generational conflict is evident throughout proceedings, with the Monserrats viewing young people with disdain and eventually as mere commodities through which they can live out their own desires.

The story uncoils in a Pete Walker-esque London – all grimy nightclubs, dingy bedsits, greasy spoon cafes and murky back alleys. The heavy stylisation dates the film somewhat, but Reeves still manages to create a few memorable moments such as the psychedelic hypnosis scene; all kaleidoscopic lighting, ferocious zooms and frenzied editing. While Reeves was only 23 when he made The Sorcerers, his view of the swinging sixties is predominately one of scorn. Aside from Karloff, characters act selfishly and without a thought of repercussion or consequence. The Sorcerers provides a subversive look at the love generation and what was to be left in its wake.

Despite what the credits say, the original story and screenplay was actually conceived and written by John Burke; however when Reeves and Tom Baker re-wrote sections of it at Karloff's request, Burke’s credit as screenwriter was relegated to ‘Based on an idea by.’

You can read more about this here.