While particularly renowned for his scores for Sergio Leone-directed Spaghetti Westerns, such as Once Upon a Time in the West and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Morricone has written film music for almost every conceivable genre. Though they are not as renowned as some of his other scores, his soundtracks for various horror films, psychological thrillers and Italian gialli are among some of the most dazzling, unusual and nerve shredding scores ever compos

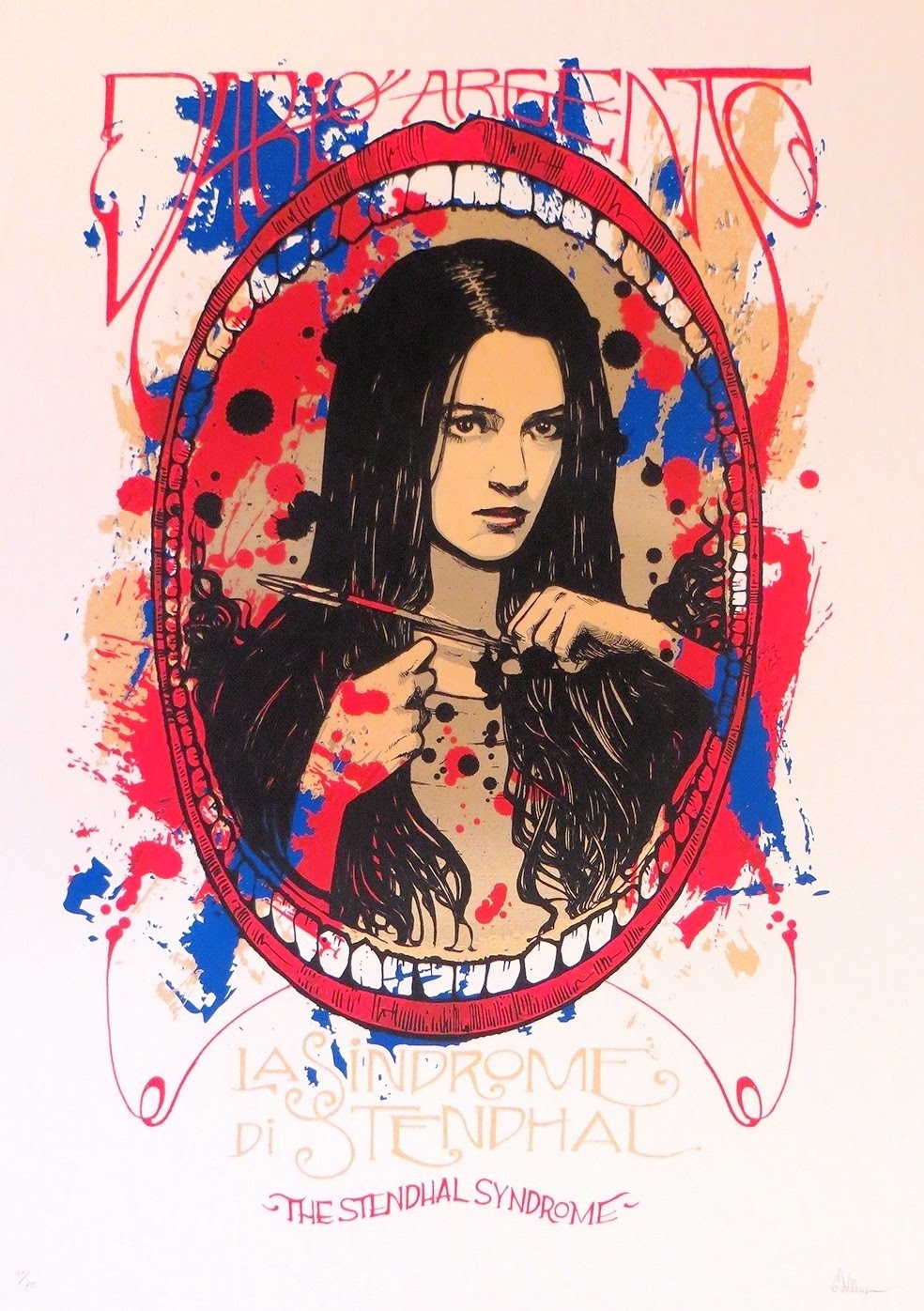

Head over to Paracinema to check out the second in a two part series in which I examine some of Morricone's musical contributions to horror films, including John Carpenter's The Thing, Mike Nichols' Wolf, and Dario Argento's The Stendhal Syndrome (pictured).

The following article was published to Paracinema.net on 20th Nov 2014

The second in a two part series examining some of Ennio Morricone's musical contributions in horror films.

Throughout the Seventies, Eighties and Nineties Morricone continued to be extremely prolific, providing music for films in every conceivable genre and working with some of cinema’s most respected directors. During this time he continued his collaborations with Sergio Leone, scoring Fistful of Dynamite and My Name is Nobody, and providing experimental and frequently alarming scores for Italian gialli; which experienced a heyday in the early to mid Seventies. The term giallo, Italian for ‘yellow’, originates from the trademark covers of murder mystery crime-thriller paperbacks extremely popular in Italy at the time. The cinematic counterparts of this stylised brand of pulp fiction took Agatha Christie-like murder mystery plots and added sadistic violence, copious amounts of sex, stylish cinematography and creepy Freudian subtexts. Ennio Morricone scored dozens of gialli throughout this time, supplying unnerving atonal jazz pieces alongside lush and melodic orchestrations that seemed to sit at odds with the violent tales they accompanied. His contributions to the giallo became less prolific as that cycle of films was in decline by the late Seventies, but he still continued to compose music for various horror titles.

In the late Seventies, and throughout the Eighties, Morricone received several Academy Award nominations for Best Score for his work on Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1979), Roland Joffé’s The Mission (1986), and Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987). Despite receiving such critical accolades, the composer continued working in genre films outside the mainstream and rarely appeared to turn down work. Throughout the Nineties and right up to more recent times, the composer is just as prolific, though his dalliances in horror cinema much less frequent. His music for genre films has been reused by filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino (Kill Bill I & II, Inglourious Basterds, Death Proof and Django Unchained) and Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani (Amer and The Strange Colour of Your Body’s Tears) to haunting effect. This has arguably introduced a whole new generation of genre movie fans to his more obscure music.

Who Saw Her Die? (1972)

When a young girl is heinously murdered in the shadowy streets of Venice, her father, a renowned sculptor, and her mother begin their own investigation when the police fail to uncover any clues. The deeper they delve, the higher the body-count rises as the crazed slayer swiftly dispatches anyone who strays too close to uncovering their identity. Morricone’s score for Aldo Lado’s chilling Venice set giallo, the title of which comes from the chant of a children’s game the little girl is seen playing before she is murdered, is comprised of choral pieces boasting a cacophony of inter-woven voices swirling and flitting like startled birds in flight. It immediately conjures images of the innocence of childhood and is shot through with an alarming urgency that becomes increasingly sinister, disorientating and panicked as the layers of voices increase. A potent and rhythmical bass line usually signifies the killer’s presence, and the use of church organs adds an element of the ecclesiastical to events. The soundtrack as a whole adds undeniable poignancy to what is essentially a striking, underrated film that riffs on similar ideas and motifs found in Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now.

Spasmo (1974)

When they are targeted by a mysterious assailant, whom they appear to kill in self defense, a young sexed-up couple seek refuge in a secluded sea-side castle. Here they encounter an old man and a mysterious young woman, who may or may not know something about the couple’s stalker. Umberto Lenzi’s mind-bogglingly confusing psychological thriller boasts an incomprehensible plot, shockingly incompetent dialogue and more plot twists than you can shake a mannequin’s severed arm at. It also features some striking imagery and a highly effective score by Morricone. A rather typical affair, this score often veers between lush, melancholic arrangements and nerve-bothering abstract discordance. The melodic title track is comprised of harpsichords, strings, acoustic guitar and woodwind, and is a breezy yet strangely moody affair. The variations of Stress Infinito often reach fever pitch, with their creeping baselines, ominous woodwind, blasting brass, stabbing strings, weird electronic effects and discordant piano and guitar. The perfect sounds to accompany, or indeed induce a nervous breakdown, and most fitting given the revelation at the climax of an otherwise lacklustre film.

Night Train Murders (1975)

Another Aldo Lado film, another atmospheric Ennio Morricone score. Inspired by Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left, Night Train Murders follows a pair of psychotic hoodlums who hook up with an equally demented nymphomaniac on a night train bound for Italy, and terrorize two young girls who soon run out of places to hide. This score is a throwback to Morricone’s harmonica-heavy Spaghetti Western soundtracks, particularly that of Once Upon A Time in the West, and is every bit as engrossing and atmospheric. Dread-fuelled tension pervades this shocking flick from the opening scene, and frantic percussion mimics the sound of a train hurtling over tracks and into madness, while a pounding piano riff maintains the suspense. Morricone’s signature harmonica motif is repeated throughout to haunting and increasingly suspenseful effect. Indeed, the harmonica theme becomes a diegetic aspect of the narrative, as it is frequently played, and whistled, by the sadistic thug, Curly. While it may lack the power of Craven’s film, particularly once the vicious trio disembark from the train and become the unwitting guests at the home of one of the murdered girl’s parents, it’s still a tautly constructed, claustrophobic thriller with a real mean streak running through it.

The Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977)

As one of the most acclaimed and controversial horror films of all time, William Friedkin’s The Exorcist was always going to be a tough act to follow. Director John Boorman’s ridiculed sequel picks up four years after the events of the first film, as Regan MacNeil realises the demon that formerly took possession of her, still lurks within her. Meanwhile, a priest investigates the death of the girl’s former exorcist, Father Merrin, and the legitimacy of the exorcism he carried out in the MacNeil house. Giant locusts, ridiculous pseudo-science and filthy language follow. The one thing most critics agreed on was that Morricone’s breathtaking score was largely wasted in such a misjudged and clunking film. The hauntingly beautiful lullaby that is Regan’s Theme wouldn’t seem out of place accompanying the stunning vistas and sweeping landscapes of a Leone Spaghetti Western, with heart-achingly ethereal vocals, gentle guitar melodies and lush string arrangements – evidence that the quality of Morricone’s music sometimes surpassed that of the films it appeared in. Tribal rhythms and connotations of primitive rituals and excesses of the flesh are evoked elsewhere with frenzied vocals, ethnic percussion and shrilly excited woodwind sections. And for sheer ‘what-the-fuck?’ value, there is the insane Magic and Ecstasy with driving Bacchanalian rhythm, fuzzy guitar riff, chanting vocals, and maddening psychedelia. The Devil never sounded so damn groovy.

The Thing (1982)

John Carpenter’s genre-blending classic focuses on the bleak plight of a group of scientists in the Antarctic who are confronted by a mysterious, shape-shifting, parasitic alien that assimilates the appearance of its prey to imitate and then kill it. Isolation, paranoia, severe trust issues and some of horror cinema’s most visceral special effects ensue. Morricone composed a highly appropriate score that at times is vintage John Carpenter in everything but name. Brooding, ominous and deeply unsettling, the chilling soundtrack incorporates orchestral moments as well as Carpenter-esque drones and pulsating atmospherics. Apparently Morricone was disappointed that Carpenter, after advising that he wanted a European sound to the score, simply used the music that sounded most like his own mainly electronic compositions. Carpenter and long-time collaborator Alan Howarth even created several cues to mix in with Morricone’s. Despite the composer’s disappointment, his score for The Thing is an eerie, downbeat and foreboding one, which takes its time to weave an atmosphere of frozen terror and despair, perfectly enhancing the unshakable feeling of dread, freezing desolation and creeping paranoia that saturates the film.

Wolf (1994)

Mike Nichol’s satirical take on the werewolf film unfurls as a savage metaphor for the ‘dog eat dog’ mentality of corporate society. Jack Nicolson plays an aging, downtrodden publisher at risk of losing his job to younger, more ruthless colleagues, while his wife secretly cheats on him. To add to his woes, he is bitten by a wolf during the full moon, and as time goes on he finds his senses are heightened, he has a new lease of life (including falling for a woman young enough to be his daughter), he grows less tolerable of bullshit, and his dreams of stalking deer through the forest are uncannily real… While it downplays the aspects of horror, and ups the satire and subtext, Wolf features a beautifully orchestrated score by Morricone, perfectly highlighting the tragic and romantic aspects of the story. There’s a subtle return to jazz elements as several noir-tinged tenor sax solos waft out from the quivering strings and ripples of synth/harpsichord. With its urban jungle setting – in which pinstriped predators mark their territory – and dream-like convalescence scenes in the countryside – where Nicholson’s character grows closer to nature, and Michele Pfeiffer – Morricone’s music expertly straddles the line between civilised veneer and carnal sensuality.

The Stendhal Syndrome (1996)

After the critical mauling of Dario Argento’s US produced titles Two Evil Eyes and Trauma, the director returned home to Italy to write and direct The Stendhal Syndrome, one of his most controversial films. It tells of a young policewoman who, while on the trail of a brutal serial killer, suddenly begins to suffer symptoms of the titular syndrome – vivid hallucinations and psychological turmoil when confronted with powerful works of art. The sadistic killer uses this to his advantage as their game of cat and mouse grows increasingly frenzied. Morricone, who hadn’t scored a film for Argento since Four Flies on Grey Velvet, here provides a haunting and eerily elegant score, submerging proceedings beneath a veil of sweepingly sinister strings, nervous woodwind, and creepy yet seductive vocal arrangements. As with his score for Who Saw Her Die?, Morricone experiments with voices to startling effect, building layers of throaty whispers and semi-audible rasping until reaching a nerve-shattering cacophony. Strangely for an Argento film, the psychological effects of violence on the protagonist are emphasised as much as the actual violence inflicted upon her, and the myriad voices, whispers and echoic effects deployed by Morricone perfectly convey her increasingly paranoid mindset.