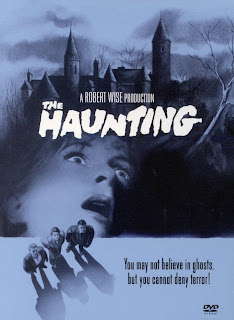

The Haunting

1963

Dir. Robert Wise

A parapsychologist seeking proof of the existence of the supernatural invites a select group of people to join him at the reputedly haunted Hill House. Once there, the group experience sinister events that not only threaten their sanity, but their very lives… Are these occurrences the result of a genuine haunting, or are they conjured by the unstable mind of one of the guests?

Director Robert Wise was a protégé of Val Lewton’s in the 1940s, and made his directorial debut on Lewton’s production of Mademoiselle Fifi, before working on the moody horror films Curse of the Cat People and The Body Snatcher. Shortly after he filmed West Side Story, Wise thought it high time he paid tribute to the man who gave him his start in the film business. In Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, Wise found the perfect blend of understated horror, fractured psychologies and icy atmospherics with which to pay homage to Lewton and the low key, suggestive horror of his 1940s 'terror' films. He was also wise enough to remain faithful to Jackson's masterful novel. The horror throughout The Haunting is conjured by nuanced subtlety instilled in Wise by his former teacher. Strange noises emanating from within the house, off-kilter camera angles to enhance the strange atmosphere and crisp black and white cinematography, courtesy of Davis Boulton, that accentuates every shadow, all combine to chilling effect throughout.

Like in most classic haunted house films, the imposing house in this film is also a character in its own right. Throughout the screenplay various conversations and dialogue between characters work to personify the house – Eleanor (Julie Harris) whispers lines such as “It’s staring at me” and “It’s waiting for me”, while the opening narration explains that the house was “born bad.” It also has a rich history which adds to its formidable reputation – madness, suicide and mysterious deaths have plagued its inhabitants. Odd camera angles suggest something is always present and watching the guests, particularly Eleanor, and the use of creepy sound effects elicits moody suspense. The interior of the house is incredibly atmospheric; long dark hallways and giant rooms seem to swallow up the people who wander through them. That Wise decided to film The Haunting in black and white during a time when colour was very much in vogue, really adds to its striking look.

The group, with the exception of Luke (Russ Tamblyn) – who is set to inherit the house - were chosen because they all experienced supernatural occurrences and exhibit strange psychic tendencies; Theo (Claire Bloom) has ESP, while Eleanor was spooked by a violent poltergeist when she was a young girl: an event she is still in denial of. Time is spent developing the characters and exploring group dynamics before proceedings plunge into outright terror. To begin with, the group, with the exception of Dr Markway (Richard Johnson), are sceptical about the reputed haunting of the house. Markway utilises a scientific approach to his investigation which results in rational explanations offered for the weird occurrences which abound within the walls of Hill House; though he does warn that a closed mind is the worst form of defence against the supernatural. They suggest that as the building is made up of weird angles, doors are hung off centre so appear to close when no one is looking, and draughts contribute to the odd cold spots felt in various rooms and hallways. Dialogue is used to evoke a sense of foreboding too, as talk of phantom dogs, ghostly muttering in the night and the suggestion that whatever stalks throughout the house is actively trying to separate the group, adds to the ominous tone.

The Haunting unravels not just as a haunted house yarn, but a detailed character study. Eleanor is a fascinating, wonderfully complex character. She is our way into the story and we’re privy to her thoughts through several segments of narration. She’s a neurotic, compelling, and unconventional character. While she is obviously flawed and sometimes not even particularly sympathetic, she is also determined to live her life and to be independent. Eleanor has spent her adult life caring for her ill mother and has led a joyless, sheltered existence, longing for independence. She is buttoned-up and repressed, and we learn that when she was young, she was plagued by a poltergeist. Given her adolescent age when this happened, the possible haunting becomes bound up in notions of traumatic sexual awakening, much like it did in The Exorcist and Poltergeist, with the onset of puberty and eventual sexual repression connected to the sinister occurrences. Internal monologue sheds more light on what makes her tick. She is uptight and neurotic, but she knows it and it fuels her need for acceptance.

Dir. Robert Wise

A parapsychologist seeking proof of the existence of the supernatural invites a select group of people to join him at the reputedly haunted Hill House. Once there, the group experience sinister events that not only threaten their sanity, but their very lives… Are these occurrences the result of a genuine haunting, or are they conjured by the unstable mind of one of the guests?

Director Robert Wise was a protégé of Val Lewton’s in the 1940s, and made his directorial debut on Lewton’s production of Mademoiselle Fifi, before working on the moody horror films Curse of the Cat People and The Body Snatcher. Shortly after he filmed West Side Story, Wise thought it high time he paid tribute to the man who gave him his start in the film business. In Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, Wise found the perfect blend of understated horror, fractured psychologies and icy atmospherics with which to pay homage to Lewton and the low key, suggestive horror of his 1940s 'terror' films. He was also wise enough to remain faithful to Jackson's masterful novel. The horror throughout The Haunting is conjured by nuanced subtlety instilled in Wise by his former teacher. Strange noises emanating from within the house, off-kilter camera angles to enhance the strange atmosphere and crisp black and white cinematography, courtesy of Davis Boulton, that accentuates every shadow, all combine to chilling effect throughout.

Like in most classic haunted house films, the imposing house in this film is also a character in its own right. Throughout the screenplay various conversations and dialogue between characters work to personify the house – Eleanor (Julie Harris) whispers lines such as “It’s staring at me” and “It’s waiting for me”, while the opening narration explains that the house was “born bad.” It also has a rich history which adds to its formidable reputation – madness, suicide and mysterious deaths have plagued its inhabitants. Odd camera angles suggest something is always present and watching the guests, particularly Eleanor, and the use of creepy sound effects elicits moody suspense. The interior of the house is incredibly atmospheric; long dark hallways and giant rooms seem to swallow up the people who wander through them. That Wise decided to film The Haunting in black and white during a time when colour was very much in vogue, really adds to its striking look.

“The dead are not quiet in Hill House.”

The group, with the exception of Luke (Russ Tamblyn) – who is set to inherit the house - were chosen because they all experienced supernatural occurrences and exhibit strange psychic tendencies; Theo (Claire Bloom) has ESP, while Eleanor was spooked by a violent poltergeist when she was a young girl: an event she is still in denial of. Time is spent developing the characters and exploring group dynamics before proceedings plunge into outright terror. To begin with, the group, with the exception of Dr Markway (Richard Johnson), are sceptical about the reputed haunting of the house. Markway utilises a scientific approach to his investigation which results in rational explanations offered for the weird occurrences which abound within the walls of Hill House; though he does warn that a closed mind is the worst form of defence against the supernatural. They suggest that as the building is made up of weird angles, doors are hung off centre so appear to close when no one is looking, and draughts contribute to the odd cold spots felt in various rooms and hallways. Dialogue is used to evoke a sense of foreboding too, as talk of phantom dogs, ghostly muttering in the night and the suggestion that whatever stalks throughout the house is actively trying to separate the group, adds to the ominous tone.

The Haunting unravels not just as a haunted house yarn, but a detailed character study. Eleanor is a fascinating, wonderfully complex character. She is our way into the story and we’re privy to her thoughts through several segments of narration. She’s a neurotic, compelling, and unconventional character. While she is obviously flawed and sometimes not even particularly sympathetic, she is also determined to live her life and to be independent. Eleanor has spent her adult life caring for her ill mother and has led a joyless, sheltered existence, longing for independence. She is buttoned-up and repressed, and we learn that when she was young, she was plagued by a poltergeist. Given her adolescent age when this happened, the possible haunting becomes bound up in notions of traumatic sexual awakening, much like it did in The Exorcist and Poltergeist, with the onset of puberty and eventual sexual repression connected to the sinister occurrences. Internal monologue sheds more light on what makes her tick. She is uptight and neurotic, but she knows it and it fuels her need for acceptance.

Eleanor appears to develop a fondness for Dr Markway, like a student may have a crush of their professor. Is she in love with him? Does she interpret his kindness for something else? Nelson Gidding's screenplay is carefully ambiguous, but it does convey Eleanor's naivety. Interestingly, when she realises Markway is married, things take a turn for the worse in the house, and her hope of a fresh start drastically dims. Eleanor’s relationship with Theo (Claire Bloom) is also an interesting one, and provides the film with yet another suggestive facet open to interpretation. The conversations between the two women, and Theo’s apparent jealousy of Eleanor’s childish crush on Dr Markway, understatedly suggest Theo’s lesbianism. When she confronts Eleanor about her feelings for Markway, Eleanor defensively refers to Theo as "unnatural," referring either to her psychic abilities, or to her implied attraction to Eleanor. Nothing is ever explicit, it's all subtext, but these moments provide the characters with so much depth and nuance. In any other film, the self-possessed and confident Theo might eventually end up in bed with man-about-town Luke. Not so in The Haunting.

Wise’s suggestive approach results in various ambiguities, such as whether or not the haunting is paranormal, or psychological. Far from detracting from the impact of the goose bump-inducing horror conjured in later scenes, this ambiguity adds to the complexity of the film. A number of moments exemplify Wise’s subtle approach to spine-chilling effect, such as the scene that follows Eleanor and Theo’s decision to share a room as they were spooked by loud noises the night before. During the night, Eleanor awakens to hear what sounds like a child being severely reprimanded by a booming voice in the next room. Terrified, she insists that Theo holds her hand, and as the noises continue and moonlight on patterned wallpaper creates demonic faces, Eleanor realises that it isn’t Theo holding her hand…

Wise’s suggestive approach results in various ambiguities, such as whether or not the haunting is paranormal, or psychological. Far from detracting from the impact of the goose bump-inducing horror conjured in later scenes, this ambiguity adds to the complexity of the film. A number of moments exemplify Wise’s subtle approach to spine-chilling effect, such as the scene that follows Eleanor and Theo’s decision to share a room as they were spooked by loud noises the night before. During the night, Eleanor awakens to hear what sounds like a child being severely reprimanded by a booming voice in the next room. Terrified, she insists that Theo holds her hand, and as the noises continue and moonlight on patterned wallpaper creates demonic faces, Eleanor realises that it isn’t Theo holding her hand…

In what is perhaps the most memorable moment, and one that certainly seems to crush any remaining ambiguity, the four are huddled in the study, taking it in turns to stay awake and keep watch, only to be tormented by a presence that thunders down the hallway outside and pushes up against the door trying to get at them. The shots of the door buckling under the weight of some unseen, ghastly force are effectively realised and unforgettable, and the ear-splitting sound effects become pulse-pounding. Little details scattered throughout the mise-en-scene add to the uneasy atmosphere such as the ‘suffer the children’ mural on the wall of the nursery and the Byron-esque sketches of demons and tortured souls in a child’s book. At one point, Eleanor even looks like the statue we see in the greenhouse earlier when she falls asleep kneeling at the couch Theo is sleeping on.

The Haunting is a masterfully constructed chiller that still retains its power to unsettle. The initially quiet, unassuming approach Wise utilises to create slow-burning tension eventually gives way to an all out, yet still credible and affecting, assault on the senses. A shining example of the ‘less is more’ approach to horror, and a wholly fitting adaptation of Jackson's novel - one of the finest psychological horror stories ever published. One to watch alone with the lights off…