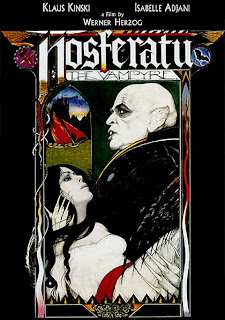

1979

1979Dir. Werner Herzog

AKA Nosferatu the Vampyre

Estate agent Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz) leaves his hometown of Wismar and travels to Transylvania to complete a property sale for Count Dracula (Klaus Kinski). When Dracula sees a photo of Jonathan’s wife Lucy (Isabelle Adjani) he is captivated and determines to find her. Drinking Jonathan’s blood and locking him in the castle, the Count departs for Wismar, bringing with him plague-infected rats. As the inhabitants of Wismar fall victim to the plague and to the Count’s thirst for blood, Lucy realises she must take matters into her own hands to save her soul and that of her traumatised husband…

Werner’s Nosferatu is a respectful and masterful remake/homage to F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens. Murnau couldn’t obtain permission to adapt Bram Stoker’s seminal novel Dracula, so he went ahead and crafted his film anyway – altering it slightly so as to avoid prosecution. A law suit was still filed by Florence Balcombe, Stoker’s widow and literary executer, and all prints of the film were ordered to be destroyed. Luckily, a few survived and the film is now regarded as an early classic of German Expressionist and horror cinema. Indeed, Herzog considers it to be one of the finest examples of German cinema and his respect for the source material is obvious throughout his own version of the film.

The film opens with astounding imagery - morbid and strangely beautiful (an apt description for the film as a whole) with various shots of preserved, petrified corpses, grinning grotesquely from their dark eternity. From the outset, the film is moody, solemn and conjures a striking otherworldly atmosphere. Herzog pays homage to the original film but is careful to also stamp it with his own sensibilities. A number of iconic shots are not repeated, instead Herzog creates a few more of his own. The shot of the Count floating dreamlike over the bow of the ship and seeming to hover for a moment as his clawed hands move slowly through the night air, is as beautiful as it is chilling. Another unnerving and wonderful moment occurs as Lucy sits in front of her mirror brushing her hair. A dark shadow seems to move across the room and her door closes – out of nowhere the Count appears at her side. The very magic of cinema seeps out of the film during scenes like these.

Moods and emotions are created and conveyed through facial expressions, hand movements and Herzog’s artful framing devices. This is a very painterly film that abounds in exquisitely framed and composed shots. The actors are placed precisely in their shots and all of them seem to utilise highly expressionistic acting; indeed dialogue throughout the film is markedly sparse.

Kinski is a revelation. His Count Dracula is one of cinema’s most interesting vampiric carnations – fully aware of his own immortality and the pain and silent resignation it brings. Unable to grow old and die, at times it appears his ‘condition’ is a curse he longs to be free of. His associations with plagues and rats and disease carriers is also quite an interesting one, conjuring vampirism as an infectious illness metaphor. His hand gestures alone are able to convey his character’s sense of pain and solitude, as they slowly dance about in the air, spider-like and theatrical. While he appears deeply melancholy, he is also devastatingly threatening – an interesting dichotomy that Kinski takes in his masterful stride. Meanwhile, Adjani also delivers a masterful performance, providing Lucy with a strong-will and determination. Her eyes are the eyes of a silent-film actor – wide and expressive.

Herzog adds a melancholy and downright carnal edge to proceedings, and this is nowhere near as evident as it is in the film’s last scenes. The Count comes to Lucy as she sleeps – unaware of her plan to distract him until dawn. Guzzling thirstily at her throat he gorges himself on her blood and as he languidly lies on top of her, bloated with her blood, he clamps one of those spidery, skeletal hands to her breast. Her determination to save her soul and that of her husband results in the ultimate sacrifice and the film ends in the oddest manner – whilst there is bleakness and tragedy, a dark and bizarre humour is also evident.

The score of Nosferatu, courtesy of Popol Vuh, utilises traditional Georgian folk melodies and songs to breath-taking and haunting effect. Herzog apparently also asked Florian Fricke to contribute a number of compositions to the film, and the results are some of the most striking choral pieces ever produced for cinema. The opening piece, a dark and moody chorus that effortlessly conveys an unshakable sense of fear and dread gradually trickles into a lighter, almost pastoral conclusion with hints of folk lullabies and prog-rock thrown in for good measure – as kittens playing with yarn appear on screen nonetheless! The music swirls together with Herzog’s unforgettable imagery to create a spine-tingling and evocative tapestry of dark and elegant moodiness. The scene depicting Lucy wandering trancelike through the town square as the population, who have accepted their fate and decide to live the remainder of their soon to end lives in stilted and debauched celebration, descends into plague-stricken madness and anarchy is accompanied by a traditional Georgian choral piece entitled Tsintskaro that swerves delicately between unattainable majesty, deep mourning and intimate contemplation and is nothing short of moving. This piece was used by Kate Bush on her album Hounds of Love (an album that consequently contains various sublime references to horror cinema) during the penultimate track Hello Earth – a song within a conceptual narrative telling of someone who is lost at sea and slowly losing hope of rescue. Fortunately the album ends on a positive note as the narrator is rescued from the water at dawn.

Kate Bush is fantastic, isn't she?! Anyway, where was I? Oh yes. Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht is a highly atmospheric and moody film, positively saturated in a morose dread and preoccupation with decay and death. Solemn and almost theistical in its tone, the film is an unforgettable experience, by turns terrifying, deeply melancholy and hopelessly mournful and one that should haunt your thoughts long afterwards.

Trivia: The part of Van Helsing was played by late Belgian writer Roland Topor, who also wrote the screenplay for the classic/cult French animation Fantastic Planet (1973) and the screenplay for the Roman Polanski’s dark and paranoid The Tenant (1976).