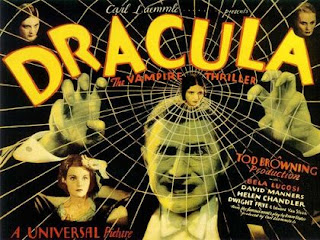

Dir. Tod Browning

Dir. Tod BrowningAfter my post yesterday about Bram Stoker and the fact that the whole of Dublin is reading Dracula this month, I found myself craving a peek at Universal’s classic adaptation of Stoker’s novel again. Featuring Bela Lugosi in his most iconic role, and some of the most memorable imagery from the whole Dracula mythos, courtesy of controlled direction from Tod Browning, Dracula is always a darkly bewitching film to indulge in.

Opening with the spooky bit from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, a highly dramatic and romanticised mood is instantly evoked. This adaptation opts to open with Renfield, not Jonathan Harker, travelling to Transylvania on business with the mysterious Count Dracula. Now seeming like rudimentary cliché, he stops off briefly at a local inn and is warned of the dastardly Count and his dubious ways. Quashing the local’s protests to turn back and ignoring their hushed whispers of ‘the Nosferatu’, he continues on his way and meets with a sinister carriage at Borgo Pass, high up in the mist shrouded mountains. This scene is hauntingly back-lit and seeps with uneasy tension.

Obvious but still exceedingly striking visual metaphors abound when Renfield reaches Castle Dracula and is invited by the Count to step through a massive spider web, and, unbeknownst to Renfield at this stage, into a world where he will eventually embrace insanity and an unquenchable thirst for blood.

The camerawork courtesy of Karl Freund, is rarely as impressive or beautifully fluid as the instance where it skulks into the crypt beneath Dracula’s crumbling castle and casts its piercing gaze at the Count’s slumbering brides rising up from their coffins and wafting through the murky chamber, wraith like. This provocative sequence is one of many highlights and each shot is elegantly composed, creating an overwhelming sense of depth, darkness and dread. It is here where we are also given our first glimpse of the imposing Count Dracula and the quiet menace he exudes.

The various performances of the cast are quite uneven. Given that the film was made in 1931 and the phenomena of synchronised sound was relatively new to cinema (The Jazz Singer was released four years prior), many of the actors still retain a silent-era mode of highly expressive acting, whilst flatly delivering their lines. David Manners (who would go on to star in The Black Cat with Lugosi several years later) is a rather stiff and starched Harker, while Helen Chandler as Mina, is sadly not given much to do except scream and faint. She is often patronised by Jonathan, particularly when she recalls a haunting dream she had about the Count advancing towards her and is told by her husband to ‘Forget about all these dreams and think about something cheerful, darling.’ Indeed this scene also holds the film’s only hint of sexual undertones as Mina breathlessly describes Dracula’s eyes and lips moving slowly towards her slender neck. ‘Where did the lips go?’ asks a flustered Van Helsing.

|

| ‘Listen to them. The children of the night. What music they make!’ |

Dwight Frye is at times a revelation as the deranged Renfield. There is a particularly blood-chilling shot of him onboard the doomed schooner as it drifts into the dock at Whitby. He is framed at the bottom of the steps leading beneath the ship’s deck, looking up at the camera, grinning and giggling manically. A later scene, shot from ground level, features him creepily crawling across the floor towards a fainted maid, the crazed grin from before is once again smeared across his gaunt face. Renfield also has some of the film’s more evocative dialogue, such as when he begs to be allowed to eat a spider. ‘I want little lives. With blood in them.’ It’s quietly haunting little flourishes like this that help elevate this version of Dracula to its classic status.

While the film does have its overtly dated and rather camp moments, such as the various bats on strings, rubber spiders, Dracula recoiling in horror from the crucifix and some really rather awkward dialogue, Browning seamlessly creates a haunting and downright dreamlike atmosphere. While events drift along into, at times, a sort of skewed and nightmare-like logic, elsewhere they are static and stagey (this adaptation is based upon the stage play more than the novel) and involve characters sitting, or standing, in drawing rooms having discussions. Certain bizarre shots, such as those of the armadillos and the wasp emerging from a tiny coffin in Dracula’s castle, add a touch of the weird and ‘otherly’ to proceedings and really enhance the dreamlike quality of the story.

Unfortunately, after building up such a foreboding sense of tension, the film seems to just stop and evil is all too suddenly vanquished. Even so, Browning’s Dracula remains a hauntingly beautiful and nightmarish film that still proves irresistible viewing today…

When Universal released their 'Classic Monster Collection' boxset, one of the special features included is the option to watch Dracula with an alternative soundtrack courtesy of Philip Glass and the Kronos Quartet. It proves a mesmerising score and its frenzied and hypnotic strings add to the darkly elegant ambience of the film. A classy delight.