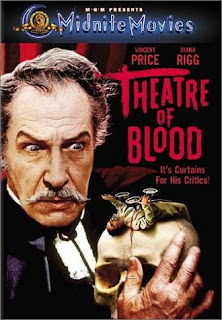

1973

1973Dir. Douglas Hickox

Edward Lionheart (Vincent Price) is a Shakespearian actor who refuses to act in anything other than plays written by the Bard. He has extreme delusions of grandeur that are eventually quashed when he is panned by an influential circle of critics and is publically humiliated at an award ceremony. Faking his own suicide in order to return and have his revenge, he gathers together a merry band of misfits to aid him in his opulent quest to obtain bloody vengeance on those critics who ruined his career. Also along for the ride is his daughter Edwina (Diana Rigg), who has fun in a myriad of different roles and disguises. Ludicrous and ever more elaborate deaths mount up as two woefully inept and utterly incompetent cops attempt to track him down and learn some stuff about the Bard as they go.

Theatre of Blood has more than a few similarities with Price’s earlier ‘themed death’ film, The Abominable Dr Phibes (1971). Both films feature crazed individuals extracting bloody revenge with extravagantly themed murders – in this case, all the deaths are inspired by demises in various Shakespearian tragedies. While this film lacks the melancholic poetry of Dr Phibes, it does maintain a literary finesse and its humour is just as irreverent, camp and politically incorrect. Price is once again at the top of his game. While thoroughly deranged, his character still retains a modicum of humanity and sympathy. Price invests such knowing theatrical vigour and enthusiasm, its impossible not to enjoy the blackly humorous story as it unabashedly unfolds. In a number of scenes when we are allowed a glimpse into Lionheart’s troubled psyche, he performs several well known and evocative soliloquies from various Shakespeare plays. Price really shines in these scenes, delivering an impeccable performance laced with sorrowful pathos and a burning obsession. The sharp and humorous dialogue, with its many allusions to Shakespeare, is barbed and witty and delivered with theatrical panache by a strong cast that have just the right amount of tongue-in-cheek.

The various death scenes that are scattered throughout the film are, aside from Price’s devilishly knowing performance, the undoubted highlights. The set up to each unfurls effortlessly and with dark glee, and is only surpassed by the pay-off when it finally comes. Michael Hordern (Whistle and I’ll Come To You) is harassed and slashed to death by a bunch of vagrants, ala Julius Caesar. Arthur Lowe has his head cut off in his sleep as his wife sleeps next to him, ala Cymbeline. Another critic is drowned in a vat of wine, ala Richard III and another is tricked into murdering his wife, Othello style. Other deaths include a man having his heart cut out as a substitute for a pound of flesh (The Merchant of Venice), a woman electrocuted and fried alive with rigged heated hair rollers (Henry VI pt I) and Robert Morley is force fed his ‘babies’ – two poodles (Titus Andronicus). Some of the personas Lionheart adopts to carry out his murderous deeds are as over the top as the murders, notably Butch the hairdresser; resplendent in flares, medallions and sporting a huge permed wig. The costumes are as elaborate as everything else on display, and as Theatre of Blood was filmed in the 70s, there is an abundance of kitsch shag-pile carpet as far as the eye can see.

|

| ‘It's Lionheart alright... only he would have the temerity to re-write Shakespeare.’ |