Aided in his investigations by fellow literary luminaries Arthur Conan Doyle, Bram Stoker and his eventual biographer, Robert Sherard, the Philosopher of Aestheticism finds himself irrevocably embroiled in a series of nasty murders, the grim details of which suggest they were carried out by a vampire…

Amidst the lavish locations and copious amounts of Perrier-Jouët decadently guzzled by Wilde and co, is an irresistibly macabre mystery which will undoubtedly please those who enjoy classic murder-mystery whodunits in the vein of Agatha Christie or indeed, Conan Doyle’s own Sherlock Holmes.

To read my full review, head over to Fangoria.

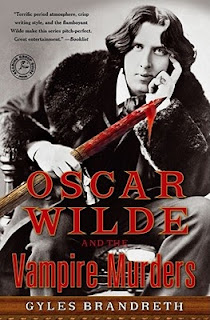

Oscar Wilde and the Vampire Murders

Unfolding in the spring of 1890, Oscar Wilde and the Vampire Murders is the 4th instalment in Gyles Brandreth’s series featuring writer/poet/wit/dandy/philosopher Oscar Wilde as a highly sophisticated, eloquent and in typical ‘Wilde’ fashion, self-indulgent sleuth. Aided in his investigations by fellow literary luminaries Arthur Conan Doyle, Bram Stoker (in the midst of researching his novel Dracula - or to use the working title he mentions in the story, The Undead – no less) and his eventual biographer, Robert Sherard; the Philosopher of Aestheticism finds himself irrevocably embroiled in a series of nasty murders, the grim details of which suggest they were carried out by a vampire.

Opening at a glamorous, High Society party hosted by the Duke and Duchess of Albemarle, we are introduced to all the main ‘players’ and suspects, including the Prince of Wales, psychiatrist Lord Yarborough and Rex LaSalle, a young actor who claims to be a vampire and who instantly captures Wilde’s attention. When the duchess is found murdered – in a genuinely creepy reveal - with two tiny puncture marks on her throat, the Prince, desperate to avoid scandal, asks Wilde and Conan Doyle to investigate the crime. What they eventually uncover threatens to destroy the reputation and heart of the monarchy.

Brandreth’s richly atmospheric and irresistible mystery unfolds through newspaper articles, telegrams, letters and dairy entries, particularly those of Arthur Conan Doyle and Robert Sherard. This serves to lend proceedings a degree of immediacy, submerging the reader within events; the separate narrations give us exclusive glimpses into the private lives of the protagonists too, really fleshing them out and making them believable as characters. As the story slow-burningly builds to its denouement, a sense of mounting urgency builds with it. The plot weaves in and out of various locations, from theatres, to restaurants, to opium dens, insane asylums, the streets of Paris, The Moulin Rouge, various hotel rooms; all the while Brandreth concocts a heady period atmosphere through his elegant prose and myriad sly references to actual events and people. A number of key moments unfurl in glorious, moodily drawn atmospheres, such as the meeting of The Vampire Club in a gloomy graveyard outside London, and the tautly constructed séance/mind-reading episode in the anteroom of the Lyceum Theatre, where the characters gather just before they discover the body of another victim. The discovery of the first victim, a lady of high society whose party the characters are guests at, is also surprisingly chilling.

Author Brandreth is a BBC broadcaster, theatre producer, novelist and biographer of Britain's royal family. His intimate knowledge of the history of the British Monarchy is utilised to the hilt and it all feels accurate and painstakingly researched, which lends Oscar Wilde and the Vampire Murders an air of credibility and authenticity. Not only does he effortlessly weave real events and people into the story, and provide a tantalizing insight of the theatrical community at the time through Bram Stoker (Henry Irving’s assistant and manager of the Lyceum Theatre), but he also peppers the dialogue with quite a lot of Wilde’s witticisms too, adding to the rich, multi-faceted feel. The result is witty and knowing, though not in a smug or deprecating manner – Brandreth obviously has a great deal of respect and admiration for his characters, and he fleshes them out with intricate strokes and flourishes. Wilde is as eccentric, larger than life and every bit as engaging as one might imagine. His more conservative, reserved foil Conan Doyle works well to maintain the balance, and their often contrasting view points provide more than a few moments of warm humour. They are essentially the ‘Holmes and Watson’ characters; indeed, humour is also derived from several instances where their investigation is compared by various characters to those of the literary sleuth’s. Robert Sherard provides the neutral voice, and is the closest thing to a narrator throughout. With such colourful, strong characters as our guides it could be easy to lose sight of the mystery at hand – but the author is careful to keep the reader on their toes, and his serpentine story twists, turns and rarely pauses for anything longer than an apéritif. Often when we least expect it, another shocking revelation or macabre clue is unearthed amongst the plethora of lavish locations, philosophising on life, love and art and the copious amounts of Perrier-Jouët decadently guzzled by Wilde and co.

Oscar Wilde and the Vampire Murders is a thoroughly entertaining and engrossing read. For those who enjoy classic murder-mystery suspense whodunits in the vein of Agatha Christie or indeed, Conan Doyle’s own Sherlock Holmes, there is much to be geekily savoured here.

James Gracey