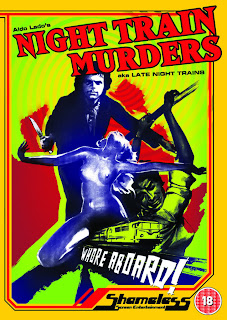

1975

Dir. Aldo Lado

AKA

L'ultimo treno della notte, The New House on The Left, Second House on The Left, Don't Ride on Late Night Trains, Last Stop on the Night Train, Late Night Trains, Last House Part II and Xmas Massacre

Two young women take a night train from Germany to Italy on Christmas Eve, and cross paths with three sadistic criminals. What follows is a gruelling night of degradation, rape and murder. In a twist of fate the murderous trio eventually encounter the parents of one of the girls. When the parents realise what happened to their daughter, they exact bloody revenge…

A loose reworking of Wes Craven’s harrowing Last House on the Left, which itself was a remake of Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, Lado’s Late Night Trains is an intense and claustrophobic experience with slow-burning, sustained suspense. Not content to just create a bloody, censor-baiting revenge yarn, Lado contemplates themes of fate, social responsibility and class conflict into the mix too, ensuring the film is not just another mindless Italo rip-off. Not that there’s anything wrong with mindless Italo rip-offs, mind you. Those familiar with the director’s other genre work, such as the unusual, stunningly shot giallo Who Saw Her Die? will know that his work is imbued with intelligence and political subtext, as well as being exquisitely photographed. The director also addressed themes of class and fate in the highly original Short Night of Glass Dolls, with its depiction of an older, elitist upper-class generation literally feeding off the younger generation.

Dir. Aldo Lado

AKA

L'ultimo treno della notte, The New House on The Left, Second House on The Left, Don't Ride on Late Night Trains, Last Stop on the Night Train, Late Night Trains, Last House Part II and Xmas Massacre

Two young women take a night train from Germany to Italy on Christmas Eve, and cross paths with three sadistic criminals. What follows is a gruelling night of degradation, rape and murder. In a twist of fate the murderous trio eventually encounter the parents of one of the girls. When the parents realise what happened to their daughter, they exact bloody revenge…

A loose reworking of Wes Craven’s harrowing Last House on the Left, which itself was a remake of Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, Lado’s Late Night Trains is an intense and claustrophobic experience with slow-burning, sustained suspense. Not content to just create a bloody, censor-baiting revenge yarn, Lado contemplates themes of fate, social responsibility and class conflict into the mix too, ensuring the film is not just another mindless Italo rip-off. Not that there’s anything wrong with mindless Italo rip-offs, mind you. Those familiar with the director’s other genre work, such as the unusual, stunningly shot giallo Who Saw Her Die? will know that his work is imbued with intelligence and political subtext, as well as being exquisitely photographed. The director also addressed themes of class and fate in the highly original Short Night of Glass Dolls, with its depiction of an older, elitist upper-class generation literally feeding off the younger generation.

Opening with impressive shots of bustling squares and thoroughfares in the heart of Munich, Lado’s camera swoops and prowls amongst the crowds, gradually singling out the film’s protagonists with repeated shots of them amongst the throngs of people; the girls - Irene Miracle (Inferno), and Laura D’Angelo - happily shopping, the two thugs - Flavio Bucci (Suspiria) and Gianfranco De Grassi (The Church) - getting into scuffles and the mysterious 'lady on the train' - Macha Meril (Deep Red) - mopping around wearing a veil, looking moody and aloof. The way the shots are cut together, the randomness of people’s actions and the paths they decide to take, highlights the idea of fate and chance and how paths are suddenly crossed and lives woven together. Of the abundance of people we see, it is the two girls, the two young men and the lady with the veil whose paths that will cross, eventually resulting in cruelty, murder and devastation.

Played with icy calm and poise by Macha Meril, ‘the lady on the train’ is clearly the one manipulating the whole sordid situation. Meril’s character echoes the members of the sect from Lado’s Short Night of Glass Dolls in her representation of the sadistic power and perverse entitlement of the upper-class elite. The first of many twists occurs when she encounters one of the thugs onboard the train, and instead of feigning off his sleazy advances, she aggressively seduces him into perverse sex with her. Spurned on by her ever outrageous and morbid demands, the young men eventually humiliate and rape the girls as the older woman presides over proceedings. The violence is for the most part, kept off screen. Sometimes, just off screen. The most graphic moment occurs when Lisa is cruelly forced to admit her virginity and is subsequently raped with a blade. One of the most unsettling, stressful moments comes when the girls violent plight is inter-cut with scenes of their parents welcoming friends to their comfortable house for dinner and drinks, oblivious to their daughter’s harrowing situation.

Morricone’s score exploits a similarly lonely and atmospheric harmonica riff as that deployed in Once Upon A Time In the West. Characters are identified by music motifs throughout, especially Curly, who actually plays the instrument onscreen, and his tune features as the main motif of the soundtrack. In one particularly taut moment, the presence of the trio of misfits is signalled by the baleful strains of his harmonica, rendered ominous by the mounting anxiety of the girls and the strangely deserted train they’re hurtling through the night in. The lighting in these scenes becomes increasingly lurid as events progress, as though mirroring the nightmarish world the girls now find themselves in.

Night Train Murders is a carefully structured, bleak and provocative thriller that in many ways highlights Aldo Lado’s unique vision and the fact that he’s a sorely overlooked genre filmmaker.

The film was banned as a video nasty in 1983 in the UK, after being rejected by the BBFC when submitted for cinema classification in 1976. Even though it was acquitted and removed from the list in 1984, it still never got a release until 2008 when it was finally passed uncut and distributed on DVD by Shameless Screen Entertainment.

Check out the trailer here.