1992

1992Dir. Bernard Rose

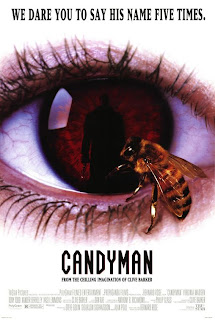

Whilst researching her thesis on urban legends, student Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen) becomes intrigued by the legend of the ‘Candyman’ (Tony Todd) – the son of a slave who was brutally tortured and killed because he fell in love with the daughter of a white plantation owner. He is said to appear when his name is spoken five times into a mirror and he has a hook for a hand. Whilst carrying out her investigation, the sceptical Helen repeats his name and is subsequently plunged into a nightmare world where reality and fevered dreams become meshed together as she is stalked by the spectre of the Candyman and held responsible for a series of grisly murders. Could the legend be true or is Helen simply losing her mind? Can she clear her name before it’s too late and she becomes the latest victim of the formidable legend that is the Candyman?

Beginning with our protagonists discussing the power of legends and the subtext of folklore, Candyman opens with a creepily familiar scenario. Babysitter waits until kids are asleep. She and her boyfriend make out. They play a variation of Bloody Mary in which they say the name Candyman into a mirror five times. While we don’t see what happens to them, the dialogue spoken by the teller of this ‘urban legend’ paints a pretty vivid picture of death and insanity. And so begins a slow burning and gripping story, made all the more compelling because of believable characters, credible performances and a well written script, which focuses as much on real, natural threat and danger as much as it does on supernatural.

Adapting Clive Barker’s short story The Forbidden, writer/director Bernard Rose relocates the story from England to Chicago – specifically its socially disadvantaged neighbourhood, Cabrini-Green. The location of the film is effectively utilised and exudes a menace all its own. As Helen and her colleague Bernadette (filmmaker Kasi Lemmons) wander through the empty apartments in the upper floors of the housing projects, we are made all too aware of the very real threats that potentially lurk in the dank corners of this concrete hell – Cabrini-Green’s reputation precedes it and many of the derelict buildings are lairs occupied by gangs. We are able to perceive a very real and tangible threat to the women, which contrasts nicely to the fact that at the same time they are in search of what they believe is an imaginary threat.

Adapting Clive Barker’s short story The Forbidden, writer/director Bernard Rose relocates the story from England to Chicago – specifically its socially disadvantaged neighbourhood, Cabrini-Green. The location of the film is effectively utilised and exudes a menace all its own. As Helen and her colleague Bernadette (filmmaker Kasi Lemmons) wander through the empty apartments in the upper floors of the housing projects, we are made all too aware of the very real threats that potentially lurk in the dank corners of this concrete hell – Cabrini-Green’s reputation precedes it and many of the derelict buildings are lairs occupied by gangs. We are able to perceive a very real and tangible threat to the women, which contrasts nicely to the fact that at the same time they are in search of what they believe is an imaginary threat. Early on in the film we hear the distressing tale of a woman who calls the police claiming the Candyman is coming for her through her bathroom wall. Her story is not believed by the operator and not long after, she is found dead, her body savagely mutilated. It turns out that someone did come through a gap in the wall behind her medicine cabinet connecting her apartment to the empty one next door, but it wasn't the Candyman. This story creates a vivid and disturbing scenario which then becomes even more disturbing because its source turns out to be a true story that became entangled with the myth of the Candyman. It also adds an extra layer of ambiguity to the story. Director Rose opts for an almost dream logic as the story unfolds and Helen’s fate mirrors that of the woman in the story – as her situation goes from bad to worse no one believes her – she maintains she is innocent and sane but less and less people believe her. Could her stories of the Candyman have a basis in reality - if only to highlight her fractured mind? Virginia Madsen delivers an impeccable performance. Helen is strong, determined, resourceful and intelligent. Yet despite all of these characteristics, she is still believably flawed and fully fleshed. She is sceptical, dismissive and snobby, and she is dominated by her philandering partner, the sleazy Trevor (Xander Berkeley). Helen does not run from the danger, she runs towards it – even embraces it in an attempt to save herself. Alas, by the end of the film, the lingering ambiguity leaves an element of doubt as to the Candyman’s actual existence. Was he real? Or just a figure of Helen’s warped psyche? The idea of Helen returning from the grave as some kind of spectral avenger is an irresistible one.

The imposing figure of the Candyman himself is one of the most unique and striking in horror cinema. Tony Todd’s baritone voice strikes nothing but dread and morbid intrigue into the hearts of the audience. He is desirable yet repellent, enigmatic and charming yet utterly dangerous – an interesting combination that is lent credence by Todd’s subtle performance and deep, velvet-voiced sincerity. At times the character comes across as something akin to saint or a martyr. Some of his dialogue is utterly evocative too – ‘I am the writing on the wall, the whisper in the classroom. Without these things, I am nothing. So now, I must shed innocent blood. Come with me. Be my victim.’ His backstory sets him up as a tragic and vengeful anti-hero – something that sets him apart from most horror villains. He was a slave who fell in love with someone society said he shouldn't love – the daughter of a white plantation owner. Something about Helen draws him to her and Rose frequently films Madsen’s eyes in ethereally lit close up shots to mirror a depiction of the Candyman’s lost love as represented in a striking mural that is revealed at the end of the film.

The imposing figure of the Candyman himself is one of the most unique and striking in horror cinema. Tony Todd’s baritone voice strikes nothing but dread and morbid intrigue into the hearts of the audience. He is desirable yet repellent, enigmatic and charming yet utterly dangerous – an interesting combination that is lent credence by Todd’s subtle performance and deep, velvet-voiced sincerity. At times the character comes across as something akin to saint or a martyr. Some of his dialogue is utterly evocative too – ‘I am the writing on the wall, the whisper in the classroom. Without these things, I am nothing. So now, I must shed innocent blood. Come with me. Be my victim.’ His backstory sets him up as a tragic and vengeful anti-hero – something that sets him apart from most horror villains. He was a slave who fell in love with someone society said he shouldn't love – the daughter of a white plantation owner. Something about Helen draws him to her and Rose frequently films Madsen’s eyes in ethereally lit close up shots to mirror a depiction of the Candyman’s lost love as represented in a striking mural that is revealed at the end of the film.  Interestingly, the Candyman is one of those figures from urban legends with a hook for a hand. This, as Julie James in I Know What You Did Last Summer so elegantly points out is a ‘phallic’ symbol embroiled in old tales to deter young people from engaging in premarital sexual relations. By casting Tony Todd in the role of the Candyman, Rose deftly weaves social commentary into an already potent mix ensuring Candyman remains one of the most thoughtful and provocative horror films since its release in 1992. It unfolds as a meditation on race, racism, class, economic poverty and the power of storytelling. The hold the gangs have over Cabrini-Green is equalled only by the hold that the area’s legends and local stories have over it. At its heart, Candyman also features a lingering 'taboo' of Hollywood cinema – an interracial relationship. Hollywood's, frankly shocking, attitude towards the depiction of interracial relationships in cinema is traceable to the Hays Code of the 30s. It out-rightly forbade any on-screen portrayal of romantic interracial relationships. In fact, marriage between people of different ethnic backgrounds only became legal in the US in the late Sixties.

Interestingly, the Candyman is one of those figures from urban legends with a hook for a hand. This, as Julie James in I Know What You Did Last Summer so elegantly points out is a ‘phallic’ symbol embroiled in old tales to deter young people from engaging in premarital sexual relations. By casting Tony Todd in the role of the Candyman, Rose deftly weaves social commentary into an already potent mix ensuring Candyman remains one of the most thoughtful and provocative horror films since its release in 1992. It unfolds as a meditation on race, racism, class, economic poverty and the power of storytelling. The hold the gangs have over Cabrini-Green is equalled only by the hold that the area’s legends and local stories have over it. At its heart, Candyman also features a lingering 'taboo' of Hollywood cinema – an interracial relationship. Hollywood's, frankly shocking, attitude towards the depiction of interracial relationships in cinema is traceable to the Hays Code of the 30s. It out-rightly forbade any on-screen portrayal of romantic interracial relationships. In fact, marriage between people of different ethnic backgrounds only became legal in the US in the late Sixties. Rose demonstrated a penchant for creating memorable imagery with his prior film Paperhouse, and Candyman is no different. It is full of arresting images including the shot of Helen climbing through a hole in the wall of a derelict apartment as the camera floats serenely back to reveal a huge mural of the Candyman; the hole in the wall, his screaming mouth. A strange atmosphere presides over proceedings and entwines the gritty and destitute urban setting with a gorgeously dark and opulently gothic foreboding. This is enhanced by Philip Glass’s hypnotic and melancholy score that becomes slightly more frenzied during scenes of suspense - it is never anything short of dramatic. Glass has ‘constructed’ one of his most underrated scores for Candyman, and one that captures and sustains the sumptuously morbid romance unfolding within the story.

Candyman remains as terrifying, visceral, thoughtful and tragic as it did upon its initial release. It seems to improve with time. Its power can be accredited not only to Barker’s vivid source material and Bernard Rose’s thoughtful screenplay and ability to conjure and sustain an air of menace and gloom, but great performances from a top-notch cast.

Candyman remains as terrifying, visceral, thoughtful and tragic as it did upon its initial release. It seems to improve with time. Its power can be accredited not only to Barker’s vivid source material and Bernard Rose’s thoughtful screenplay and ability to conjure and sustain an air of menace and gloom, but great performances from a top-notch cast. What’s more - I’ll bet you still wouldn’t stand in front of a mirror and say Candyman five times…