Interview with Wyatt Weed: Part 2

BTC: Why do you think the vampire is such an enduring figure throughout cinema?

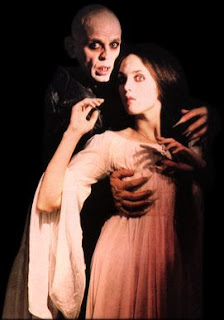

BTC: Why do you think the vampire is such an enduring figure throughout cinema?WW: Just like the mythological creatures they are based on, the fictional vampires we create are very adaptable. The vampire is one of those cinematic images that has done well with updates and re-makes. The basic story and character are solid, so every time there is an advance in sound or colour or technology, an update works very well. Vampires have gone from being talky melodramas to Technicolor blood fests and then more recently, action vehicles and teen romances, and we've even seen minority vampires.

Vampires aren't "Citizen Kane" or "Casablanca" - they can be re-worked again and again without offense to classic cinema, constantly updating with the times and changing. "Interview with the Vampire" is a brilliant practical example of this theory, a story of how a vampire changed and adapted over time, with the inclusion of many different architectural and fashion styles, languages, and influences. Vampires are creatures that have relevance over and over again, reflecting whatever social parallels you can project on them.

BTC: Obviously the locations were important to the story – how did you go about finding them? Why was it important to you to set and film the story in your home town of St Louis?

WW: I lived and worked in LA for 18 years, and even though the town is designed around production and used to it, it is expensive and doesn't always favour the independent filmmaker. When I moved back to St. Louis in 2006, it was for the express purpose of making features, because there is a great untapped pool of talent and unseen locations here. It is also cheaper and easier to get around. Once we realized we were going to be doing a vampire film, it became clear that we needed older and moodier, and St. Louis has history - a lot of the older sections of town are still functional and maintained. Beginning with some of my social visits before moving back, I just began keeping a list of interesting places I would see around town: a home here, an old office building or street corner there, a diner, etc.

The biggest compromise we made was in the church where the final showdown takes place. That was written as a crumbling structure, with the ceiling collapsing and debris everywhere. Well, there are several churches like that in St. Louis, but we couldn't get the permission to shoot there because of the dangers involved. The owners just wouldn't sign off. The compromise was to get a church and dress it to look like it was under construction.

The church in the opening, the one that is being renovated, was a very happy accident. About three or four days before we needed this location, the scaffold went up in front of this particular church and they began tuckpointing. We had thought that we would do our own set, bring in some work tables and tools, but the scaffolds they were using were huge, and these guys had a lot of gear, so when they said yes, we gained a lot of production value. All of the stuff around the church is theirs, and the guys up on the scaffold are the real workers. Basically, our technique with all of these places was to just go up and ask. The worst they could do was say no, but more often they said yes. We were always prepared though, with insurance, permits, and local municipal notification. That's very important, ESPECIALLY if you're low-budget.

BTC: It sounds like there was a lot of support on a local level.

WW: Well...yes and no. Mostly yes. For the most part, people were just so thrilled and excited to see a film get made, to be a part of it, that they opened their doors. They would sit and watch, fascinated, glued to our every move, willing to help at every step. They realized that if the film was a success, it would only help their businesses, and that other films would come and shoot there.

On the flip side of this, St. Louis isn't really a big production town yet, so some residents aren't used to the idea that their daily routine might be interrupted. For example, if we had a street blocked off, that REALLY messed some people up. Other people would loose their minds if you asked them to do a little something for the movie, like move a car out of a shot, and I mean get screaming angry! It was really crazy how mad some people got when you messed with their world just a little bit, if you moved a trash can two feet or set a light stand on the edge of their property. What it made me realize was how protective people are of their little piece of the world, and with all due respect to these people, it's something I can't identify with. I don't own a house, I haven't fought to protect it, so I don't know what it's like when someone threatens my hard earned space like that.

BTC: There are many fight scenes and transformation scenes throughout the story. How difficult was it to realize such impressive effects given the film’s low budget?

BTC: There are many fight scenes and transformation scenes throughout the story. How difficult was it to realize such impressive effects given the film’s low budget?WW: Once again, thank god for my background - I have learned to have a plan, storyboards, and all of the bases covered with options, because when it comes to filmmaking, if it can go wrong, it will.

First, we found a talented make up artist we could afford, Rachel Rieckenberg, a young woman just out of school who really needed the work and the experience. With a little guidance, she was able to do amazing things. I planned the shots very carefully in advance, so we knew how to transform in layers, shot by shot, step by step. We wanted subtle, but we wanted quality. Because we knew what we needed, we were able to make it in advance and then move forward with it fairly quickly once we got on set. We knew what the shots would be, we lit it to look good for the make up, and we didn't push any of the effects to do more than they were designed to do.

For the fights and all of the action, once again, I storyboarded everything and rehearsed it with all of the actors. If we couldn't do it on the actual location, we did it in a space that was similar. We made sure we were safe, and had crash pads available. Preparation and planning, man, that is the key to everything. If you've rehearsed it and done it, you know what it will take, and you can do it on set the day of with confidence.

BTC: How did you go about recreating early 19th century St Louis?

WW: Thankfully, there is a small town just outside of St. Louis called St. Charles, and the Main street there is a historically preserved area that is virtually unchanged from the late 1800's. All we had to do was remove or cover up a few modern touches - a speed limit sign, a modern fire hydrant, a drinking fountain, and some lighting fixtures. Boom, instant 1897! Also, there are several carriage companies in St. Louis, old horse drawn carriages with original rigging. They offer scenic rides around town, so we hired a company to bring out a horse and carriage for those scenes. That really added production value.

One other huge help was our friend Nick Strupp at the Tintypery, a studio that specializes in old style photographs. They had a supply of old costumes and wardrobe, so we were able to dress all of our background players from their stock. For the interior of Laura's house, we used an established bed and breakfast called Victorian Memories, and once again, it was dressed and set up already, with very little extra dressing to do.

Our biggest problem was that once or twice we had to digitally take a modern "Visa" logo out of the windows of some of the businesses. One note - we don't say that it was St. Louis in the film. We avoided that altogether, and purposely didn't show one of our greatest landmarks, the Gateway Arch. That was so that anyone in any major Midwestern US city could identify with the film. Once you say where it is specifically, you lock it in to a geography and a culture, and I wanted to leave it more open than that. That was why our police badges and cars said "Metro" on them instead of something more specific.

Part I of interview

Part III of interview

Shadowland is released on the Yellow Fever DVD Label in May...

Read the review of Shadowland here...