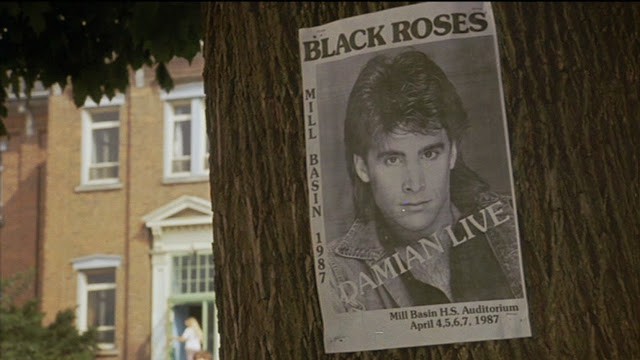

Directed by John Fasano and written by Cindy Cirile (credited as Cindy Sorrell), Black Roses tells of the eponymous metal band, fronted by the darkly charismatic Damian (Sal Viviano), who begin their world tour with several special concerts in the small town of Mill Basin. Naturally the local teens are psyched to see their favourite metallers, but their parents and the town authorities are concerned because of the band’s reputation as heavy metal hell-raisers. Turns out these parental fears are not unwarranted, as the band are actually demons whose music corrupts listeners and transforms them into minions of chaos and evil. As the town’s youth run wild and succumb to the band’s diabolical influence, it’s up to an open-minded, down-with-the-kids high-school teacher to crash the concerts and try to save the day.

Stage-diving onto screens hot on the heels of Hard Rock Zombies (1984), Trick or Treat (1986) and director Fasano’s own feature debut Rock‘n’Roll Nightmare (1987), Black Roses goes all out to exploit the diabolical connotations and Satanic imagery associated with heavy metal, not least the idea that it can corrupt the morals - indeed the very souls! - of listeners. It's a key title in heavy metal horror, a filmic sub-genre that emerged in the eighties when filmmakers tapped into and exploited the feverish backlash against the perceived Satanic threat and corrupting influence of heavy metal music on young listeners. While the idolisation of rock stars of course goes further back than the eighties, Black Roses imbues the idea of rock hero-worship with sinisterly subversive qualities, likening it to idolatry and the breaking of the first of the Ten Commandments. This is most evident in the concert scenes where teens are whipped into a frenzy, transforming into demons, and in the moment when Mr Moorhouse’s (John Martin) class starts chanting Damian’s name in an act that can be interpreted as demonic possession as well as a protest against the town’s censoring of the band.

Ideas regarding censorship and moral panic are also highlighted in other classroom scenes as the teens study the poetry of Walt Whitman, whose work - particularly the collection Leaves of Grass (1855), now considered amongst the most significant and central works of American poetry - was branded obscene upon publication due to its explicit depictions of sexuality. In his book To Walt Whitman, America (2004), author Kenneth M. Price suggests the referencing of Whitman’s poem ‘Song of Myself’ in Black Roses is used to frame the consideration of evil. Throughout the film, heavy metal music is depicted as a literal conduit of evil, and its sinister influence is revealed as vinyl records ominously pulsate, concert audiences are transformed into mindlessly violent minions of evil, and a rubber demon pops out of a stereo speaker to attack an overbearing father (Vincent Pastore from The Sopranos) and drag him into the speaker. After filming, which predominately took place in Hamilton, Ontario, Fasano and co. shot more scenes featuring monsters and gruesome prosthetic effects in New York in order to up the ante. While the puppets and effects are dated and really rather cheesy, they still retain more personality, character and soul than many of today’s CG film monsters.

Heavy metal has long held diabolical connotations and Satanic associations. From the 1963 Mario Bava horror film that gave Black Sabbath their name, to the church burnings connected to the Norwegian black metal scene, occultish imagery and devilish antics have been an integral part of metal since its inception in the late sixties. These associations actually stem back to the Blues music from which heavy metal emerged, and to the figure of Robert Johnson. Widely hailed as the King of the Delta Blues, Johnson frequently sang about his dealings with the Devil, and while these were obviously metaphors for real life struggles, legend has it that Johnson once encountered the Devil at a crossroads (a place typically regarded in folklore as being between the worlds of the living and the dead, and where contact with the spirit world is intensified). There, beneath the pale moonlight, Old Scratch tuned Johnson’s guitar and, in exchange for his soul, granted Johnson profound musicianship and stardom. In the eighties however, these associations were perceived to be more than mere myth, and Satanic Panic gave rise to the belief that heavy metal posed a real threat to the morals of America.

In was during this climate of witch hunts and extreme censorship that screenwriter Cindy Cirile was inspired to pen Black Roses. Cirile cited Tipper Gore’s allegations that heavy metal was ‘the Devil’s music’, and how it was driving teens to murder and suicide, as the catalyst for her idea of a diabolical rock band that really was from hell, and was hell bent on wrecking chaos and destruction (tellingly, a black rose was at one time used as an obscure symbol for anarchy). Black Roses may be a low budget, schlocky affair, but amongst all the cheesy guitar solos, tight leather trousers, big hair and rubber monsters, it offers interesting commentary on generational conflict, censorship, small town conservatism and Satanic Panic. Cirile’s screenplay touches upon some of the key debates surrounding the reputedly evil influence of heavy metal on its listeners. An early scene features a town meeting in which concerned parents and town officials, including Tipper Gore-like Mrs Miller (Julie Adams, The Creature from the Black Lagoon [1954]), become whipped into a fundamentalist frenzy at the prospect of the town hosting concerts of such ill-reputed music. At one point a concerned resident exclaims ‘Bad kids, bad music, bad news!’

Black Roses is very much a product of its time, and while it plays up to stereotypes of heavy metal fans - with their sullen demeanours, dark clothes, disaffected attitudes and the depiction of rock concerts as forms of civil unrest - the film also successfully taps into the fact that horror and heavy metal often share a strong fan-base. Cirile and Fasano fully understand that every generation has its form of rebellion against what they see as the morally conservative social constraints passed down by older generations, and that the more governments and parents try to prevent their teenaged children from attending concerts and listening to certain records (or watching horror films or playing violent video games), the more the younger generation will persist in its attempts to do just that. Joanne McDuffie, lead singer of the Mary Jane Girls - whose record ‘In My House’ was placed on the PMRC's 'Filthy 15' - said it best in an interview with Rolling Stone when she suggested ‘The quickest way to get your children interested in something is to try and keep it from them.’

Adding to the film’s cult appeal is its notoriously rare and difficult to obtain soundtrack album. The music performed by the band throughout the film was largely provided by members of King Kobra, a hard rock band founded by drummer Carmine Appice (older brother of Vinny, a drummer for Black Sabbath and Dio, and a co-writer of Rod Stewart’s 1978 hit ‘Da Ya Think I’m Sexy’) who also drummed with the likes of Vanilla Fudge and Ozzy Osbourne. The theme song ‘Me Against the World’ - written and performed by Lizzy Borden - perfectly encapsulates that eighties’ brand of teenaged angst and alienation.